We were conveyed to the Netherlands by a Megabus from Edinburgh, with

a change-over in London. The administration of the ride was a mess.

Somehow, the Megabus passengers to London were separated into two

different busses (neither was full to capacity), one of which (ours)

made stops in Newcastle and Leeds, which I'm not sure it was supposed

to. The drivers had disputes with bus station officials. No one seemed

to know where the passengers were supposed to get off. There was no

water or toilet paper in the bus. We were very late to London, but they

held the London-Amsterdam bus for the Edinburgh connecting passengers.

I had hoped to sleep once we switched busses in London, but we had to

all get out of the bus for the ferry ride, which was fully lit, loud,

and had nowhere to lie down. I slept a little on the ferry and the bus

afterwards, but probably only a couple hours.

On the ride, I read

How Can You Defend Those People?, an account of

James Kunen's time as a public defender in Washington, D.C. James Kunen, strangely, is the author of

The Strawberry Statement,

an influential first-hand report on the late-'60s student occupation of

Columbia University. It seemed like an appropriate follow-up to Sergio

de la Pava's

A Naked Singularity, which is also about public

defenders. Actually, de la Pava does a better job of answering the

titular question of Kunen's book than Kunen does, but I liked

How Can You Defend Those People? anyway.

We couldn't get any Couch

Surfers to host us in Amsterdam. It's a bad sign, since we're relying

on it for much of our time in Europe. Amsterdam hosts are inundated

with requests at this time of year; I'm hoping other cities will be a

little less crowded, and easier to find a host in. We booked the

cheapest available hostel, near the Oosterpark, south-east of the city

center.

The first thing we noticed about

Amsterdam was the bikes. I had heard Amsterdam was a "bike-friendly

city," in the way people say that Minneapolis or Portland, for example,

are "bike-friendly cities" because of their bike lanes, navigable

layouts, and large number of bike commuters (in Portland, the number one

city in the United States for bike commuting,

almost 6% of workers travel by bike). The difference is that in Amsterdam, bikes represent the

majority

of city traffic. The bikes are predominantly the sturdy, heavy,

classic Dutch cruiser style, which make sense in a city as flat as

Amsterdam. There are more bikes than cars. On the small streets, cars

share the road; on larger through-ways, there are wide bike lanes,

separated from the road and the sidewalk by curbs. Amsterdam should be a

model to U.S. cities seeking to improve their bicycle infrastructure.

|

| The parking garage in the background is also packed with bikes. How do people manage to find their own bikes in this mess? |

|

| The Dutch also like comically tiny cars |

After

the bikes, the second and third things we noticed about Amsterdam were

the heat and the trash. It was probably 30 degrees hotter in Amsterdam

than when we got on the bus in Edinburgh. Also, for as beautiful a city

as Amsterdam is, it's downright filthy. The canals are dirty, almost

every trash can is overflowing, and the parks are full of plastic bags,

takeout containers, bottles and cans, and cigarette cartons. It's

possible that Amsterdam's infrastructure is ordinarily better equipped

to deal with garbage, and is just temporarily overwhelmed in the height

of tourist season. Whatever the reason, the trash tarnished the city's

charm somewhat.

But what charm it has.

The famous houseboats were fantastic:

|

| Also, there was this guy |

We visited both the very beautiful

Rijksmuseum and the

Van Gogh Museum. The Rijksmuseum has been under construction for a decade or something, but most of the

hits are on display.

|

| The corrugated-metal storage container really contributes to the majesty of the place |

The collection is fairly small - all Dutch

artists, with Rembrant prominently featured. There are also a number of

Vermeers. Rembrandt is cool and everything, good grasp of light and

color, etc.,

but Vermeer has something that sets his work apart from his peers in a

way that's hard to describe. I'm too much of a boor to appreciate still

lifes and portraiture, for the most part, which constituted a lot of

the Rijksmuseum collection, but I do like Vermeer.

|

| River View by Moonlight, Aert Van der Neer |

|

| Still Life with Turkey Pie, Pieter Claesz |

|

| The Threatened Swan, Jan Asselijn |

|

| The Night Watch, Rembrandt |

|

| Portrait of Gerard Bicker, Bartholomeus van der Helst |

|

| View of Houses in Delft, Vermeer |

|

| The Milkmaid, Vermeer |

Some of my favorite things from the collection were the 16th-18th century Dutch furniture and earthenware.

|

| This is probably the cruelest cabinet in existence: tortoise-shell inlaid with ivory |

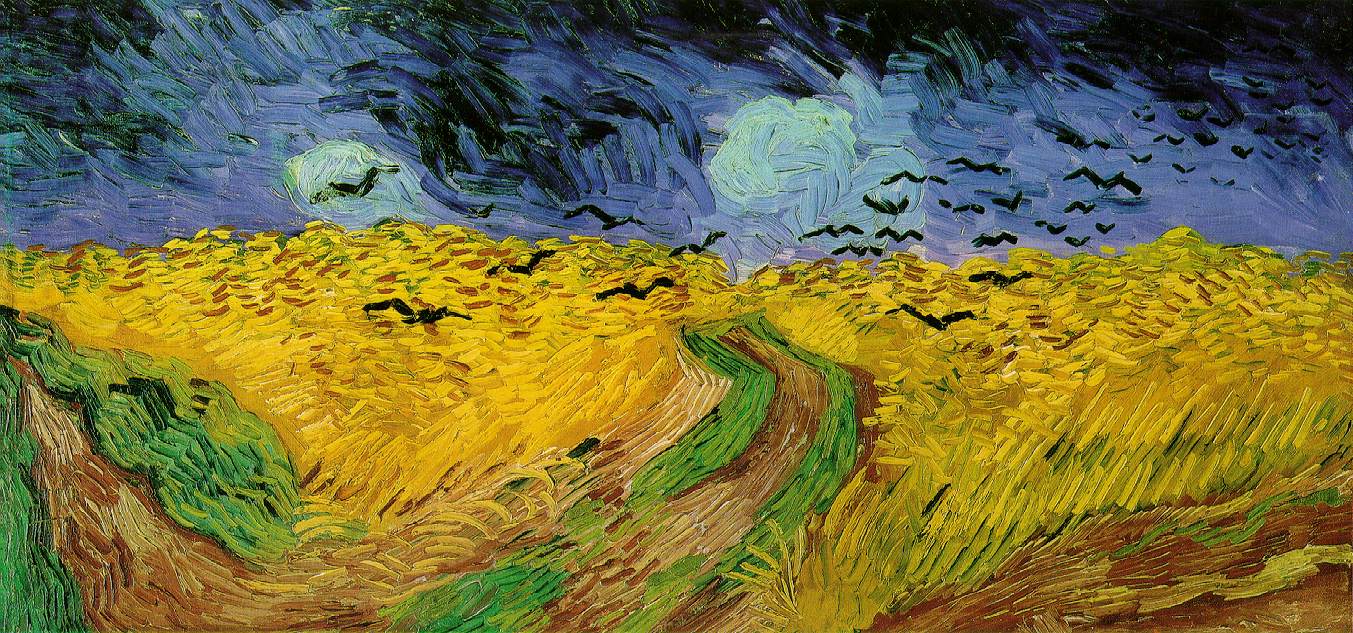

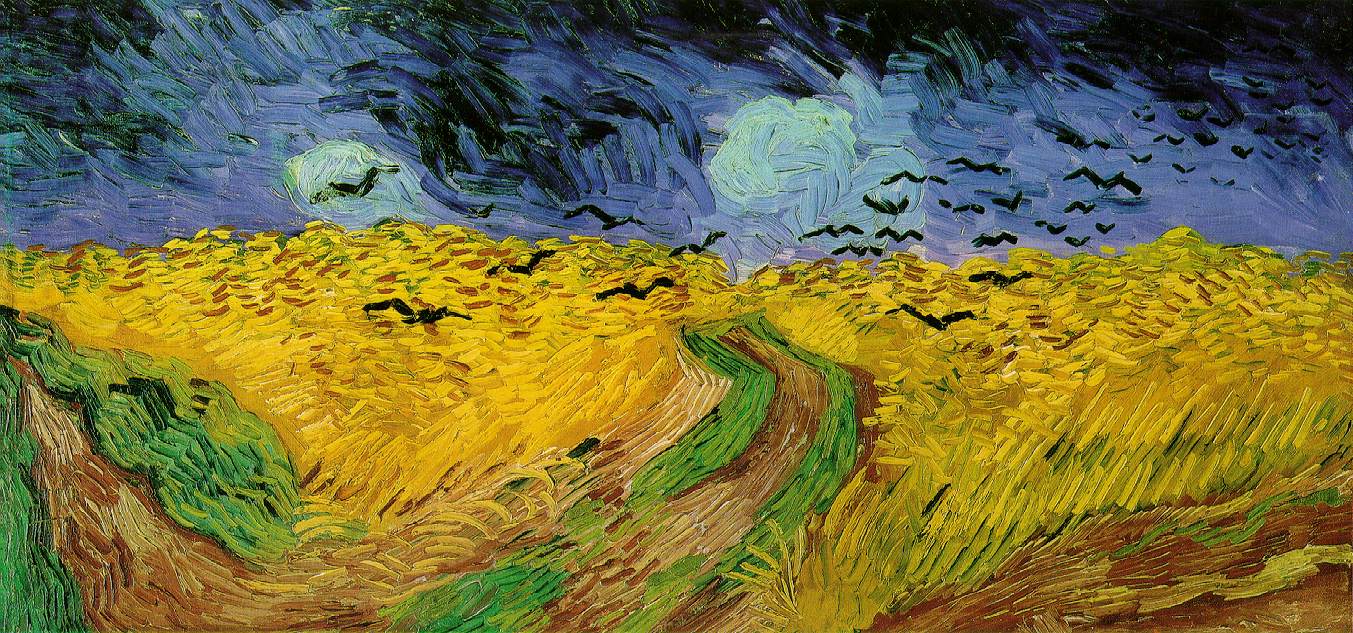

I was daunted by the line outside the Van Gogh Museum, but I'm glad I stuck with it. The queue moved quickly, and inside was some of the best art I've ever seen. Obviously, there were a huge number of Van Gogh's works from all periods of his

oeuvre.

It's arranged chronologically, beginning with his first sketches and

early still-lifes, through his brown-and-black peasant studies, to his

colorful and loose Arles paintings, and ending with his spiral into

near-abstraction in the years before his suicide. Unfortunately, there

were no photos allowed. None of the

following pictures are mine:

|

| Room at Arles, Van Gogh |

|

| Wheatfield with Crows, Van Gogh |

|

| Skull of a Skeleton with Burning Cigarette, Van Gogh |

|

| Tree Roots and Trunks, Van Gogh (possibly his final painting) |

As

fantastic as that was, I was even more pleased by the museum's

galleries of Van Gogh's contemporaries and followers. I've seen a few

Impressionism exhibits before, and it always strikes me that they

feature a lot of the artists from that movement that I like least (Mary Cassatt). This collection was all killer, no filler, and

introduced me to some artists I hadn't seen much of before and really

liked, such as Émile Bernard, Charles Laval, Alexej von Jawlensky, and

Leo Gestel (although their paintings from the Van Gogh Museum collection

aren't available in good quality on Google Image Search).

|

| Portrait of Vincent Van Gogh Painting, Gauguin |

|

| Portrait of Guus Preitinger, the Artist's Wife, Kees van Dongen |

|

| Breton Girl Spinning, Gauguin |

|

| La Recolte des Foins, Éragny, Pissarro |

There was also a stupendous exhibit of

fin de siècle prints

by artists such as Édouard Vuillard, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Pierre

Bonnard, Félix Vallotton (my new favorite artist), and Jean-Émile Laboureur. Once again, some of the best weren't available online:

|

| Trottoir-Roulant, Vallotton |

|

| La Manifestation, Vallotton |

|

| La Petite Blanchisseuse, Bonnard |

|

| Saint-Tropez II, Signac |

|

| Tiger in the Jungle, Paul Ranson |

Although the Van Gogh Museum contained a lot of excellent material, it's pretty small. We only spent a few hours there.

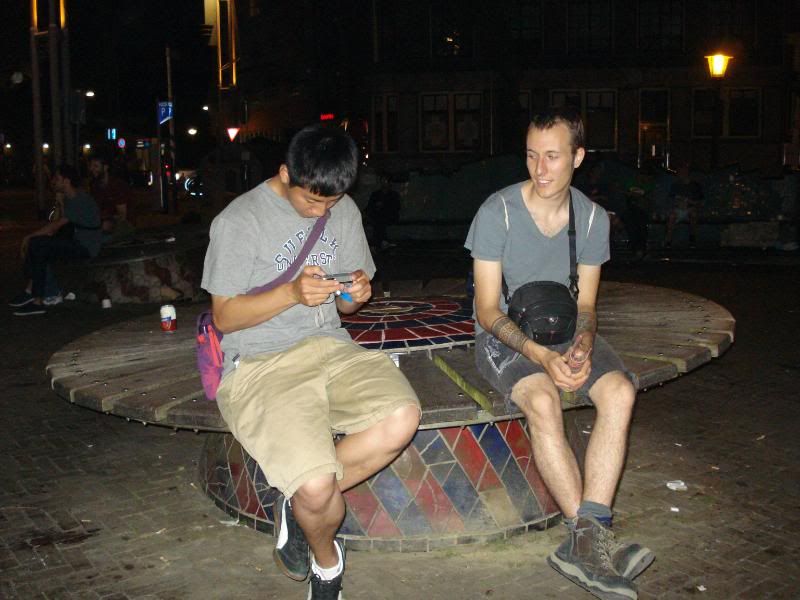

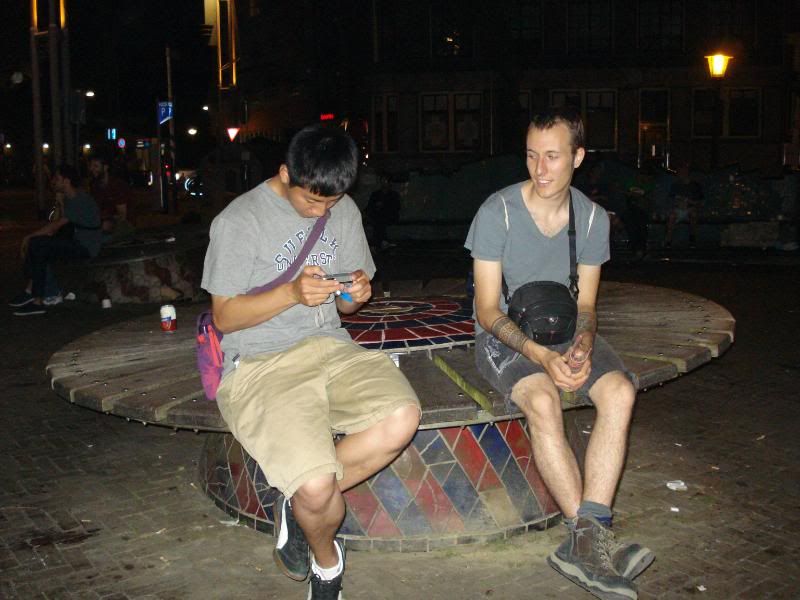

We did pass through the Red Light District, almost reluctantly. At our hostel, we met another American, Ryan, who's studying in London

and had just arrived in Amsterdam a few hours before, and the three of us went to see what it was about. It was sort of interesting, but

less than I expected. Perhaps it's because the

prostitution seems so un-seedy, safe, and efficient. The girls, at

least the ones in the windows, are suprisingly pretty and don't seem desperate, although this is probably an illusion - most of the prostitutes are foreigners without much education, often trafficked in from Eastern Europe by unscrupulous pseudo-pimps. Most people in

the neighborhood were tourists, like us, there out of curiosity, or to

buy marijuana and overpriced beer. The seedy aspects were much the same

as the ones you'd expect from a large college campus on a Saturday

night. There were bros, or the European equivalent thereof, as

far as the eye could see. We passed through one alleyway where an

obviously beleaguered resident had put up signs imploring (in English,

Dutch, and via illustrations) passers-by not to urinate, vomit, or shit

on their doorstep. That there must have been enough bodily fluid incidents in this single alleyway to necessitate

multi-lingual signage is a testament to how mind-bogglingly awful the

Red Light District is.

|

| Ryan and me in the Red Light District |

On Monday, we picked up bread and a tomato tapenade for a picnic brunch

on our way to rent bikes. I wish we hadn't pushed the bike rental back

to our last full day in Amsterdam, because it was a total joy, and an

excellent way to get around the city (the drawback is that it costs

something like 15 euros for 24 hours, or 9 euros for 3 hours - ouch).

We biked through the famous Jordaan neighborhood, filled with

17th-century row houses converted to galleries, coffee shops, and

antique stores. We ate in a green space next to a house-boat.

We

biked past a couple of squats on Spuistraat, covered in graffiti and

slogans.

I felt somewhat melancholy. The Netherlands are the Mecca of

squatting. Until 2010, it was essentially

legal to occupy abandoned buildings.

Squatting is something I've always been interested in, at least in principle. I don't have a very friendly relationship with the capitalist economy: I did everything I was supposed to to appease it, and yet it seems intent on burying me. Squatting offers an out from the tyranny of the paycheck, and so I like it. It also makes simple sense: there are thousands of buildings that

municipal governments have possessed for non-payment of taxes standing

empty in the U.S., deteriorating until the city sees fit to use your tax

dollars to demolish them. I am a person who wants to occupy and

improve these buildings. This seems eminently reasonable, and yet the

law holds that this a crime. I'm digressing: the point is that a few years

ago, I would have been really excited to see Amsterdam's squats, but

now, I hadn't even thought about it and would've missed them entirely,

had my touristy bike route not accidentally led me past them. I would

love to meet some squatters and gain some knowledge about the practical

aspects of squatting, but I don't even know where to begin to do that.

I'm not politically radical enough, for one thing, and I feel like I've

become so comfortable in my role as a young urban working guy (or

whatever) that I would seem disconnected and soft to squatters. I now

feel like I'll always be an outsider to that scene, and that's sort of a

sad thing to come to grips with. It's a strange feeling to have a

dream die, not because you're no longer interested, but because you

recognize the reality that you can't be the kind of person who can make

that dream happen, the kind of person you thought you were.

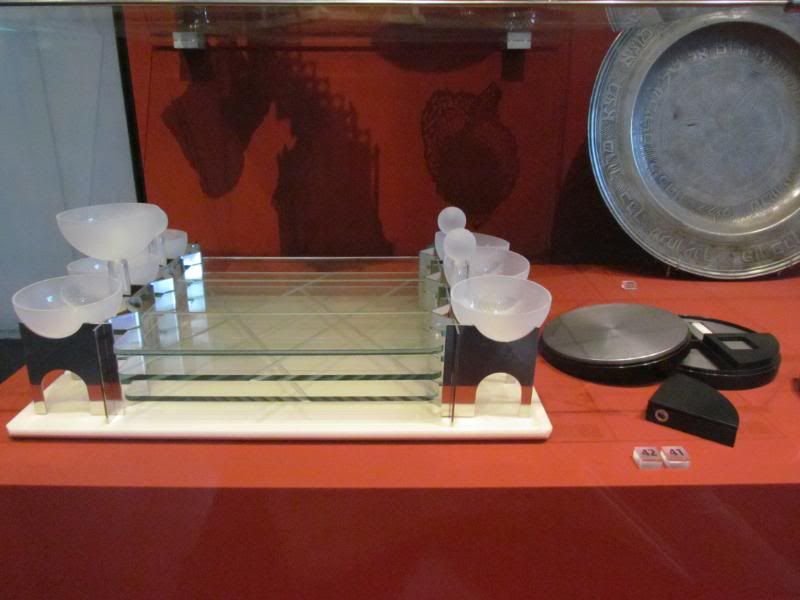

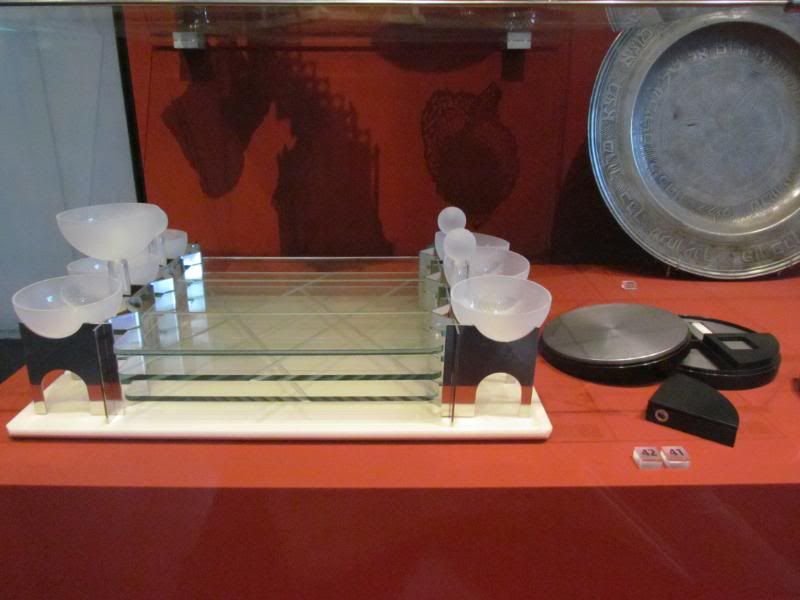

Our biking route was haphazard, but that was the idea from the start. We returned the bikes and walked to the

Jewish Historical Museum,

which is housed in a former synagogue. In the basement was a

collection of Jewish artifacts ranging from 17th century Torah finials

to 1920s art deco seder plates.

|

| Circumcision toolbox |

|

| Modern clock |

|

| Seder plate. The thing on the right is a light to aid in the ritual of searching out your last crumbs of chametz before Passover |

Ascending to the ground level and second story, the museum presented a

history of Dutch Judaism. Unexpectedly, three Marc Chagall paintings were on

temporary loan from some or another foundation, shoehorned into a

section of hallway near the old synagogue's

mikveh.

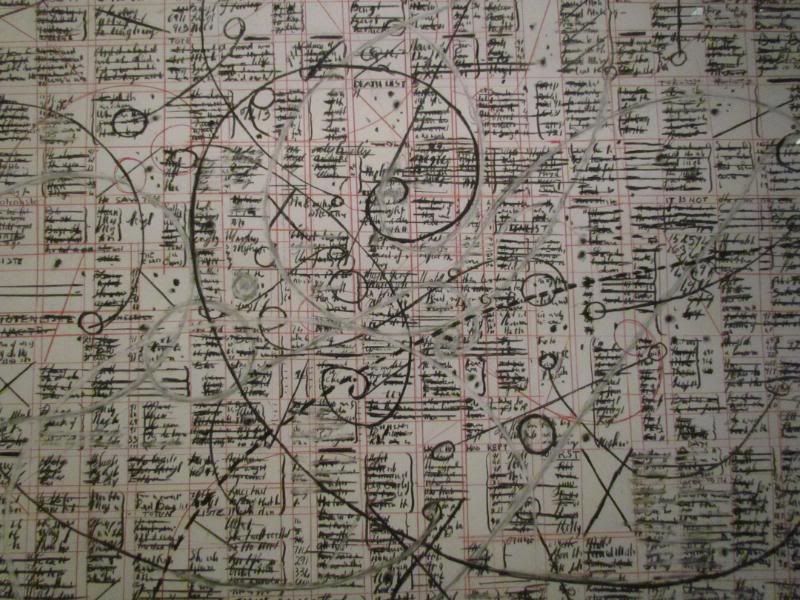

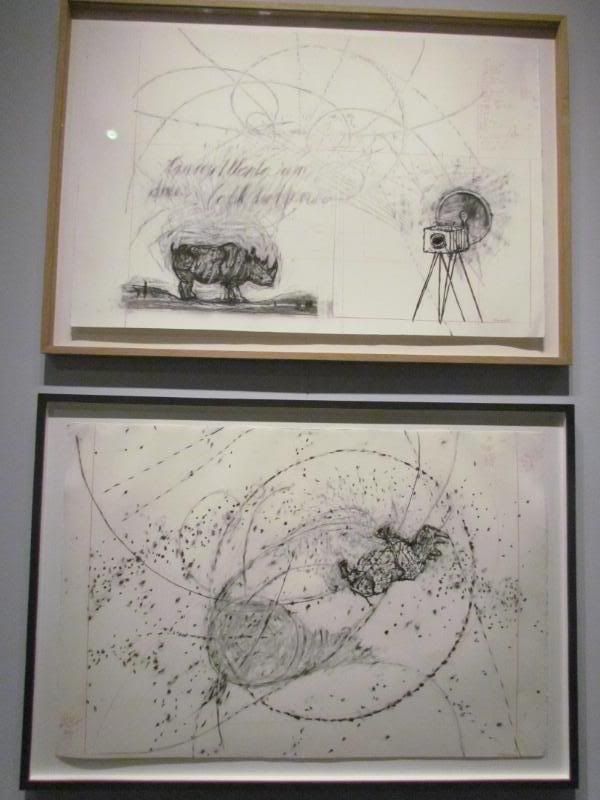

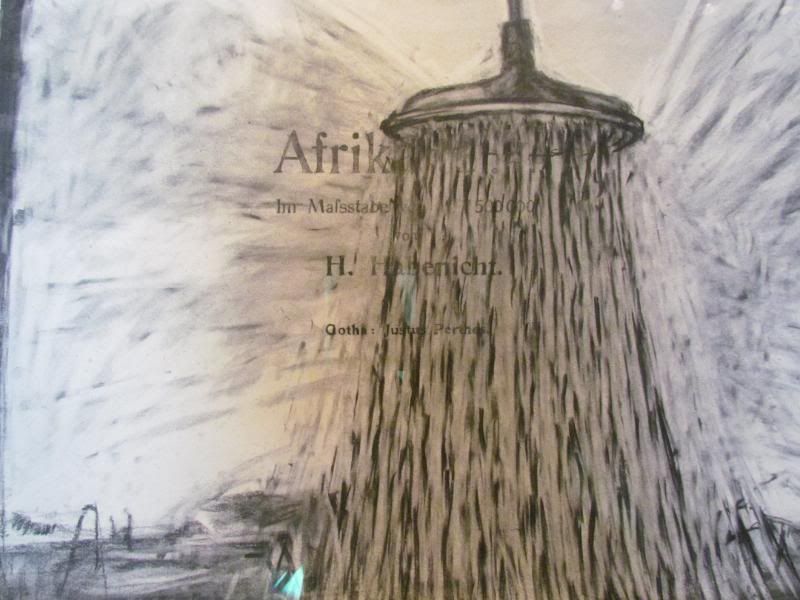

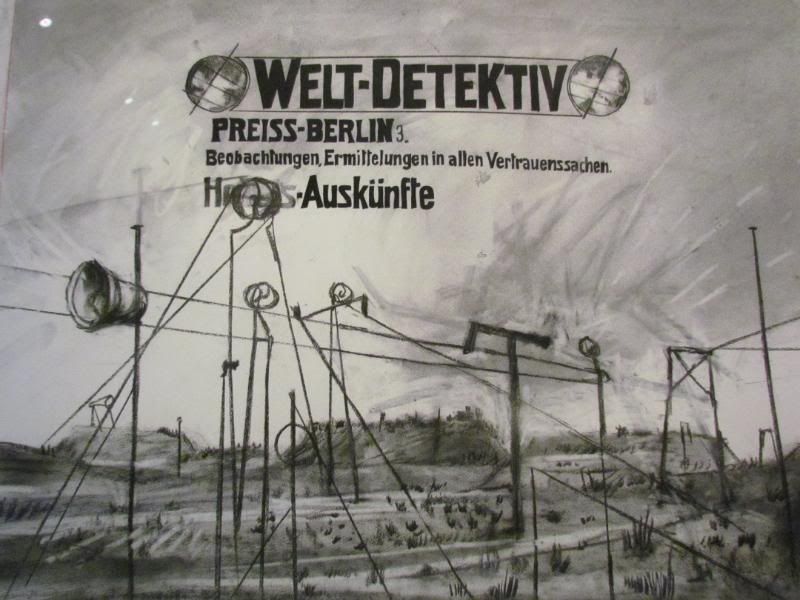

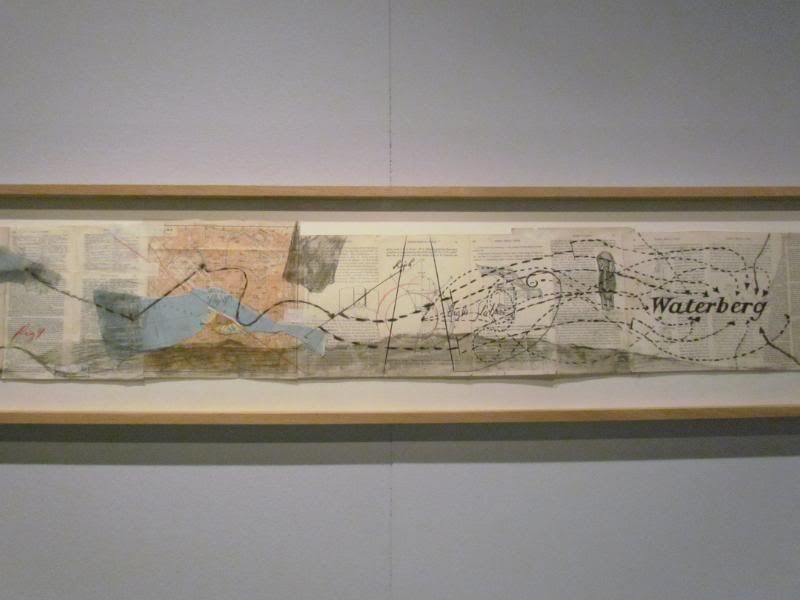

The most interesting part of the museum was a multimedia installation by

William Kentridge,

Black Box. Kentridge is a white South African Jewish artist whose work is highly political, as that complex ancestry might imply.

Black Box is a commentary on the

genocide

committed by German colonial forces against the rebelling Herero and

Namaqua peoples of Namibia. The work consists of mechanized figures

moving over a projected backdrop of Kentridge's animated charcoal drawings and historical

documents from the colonial period, set to Namibian music. The stated concept of the work was

to examine how Enlightenment ideals of human equality were twisted to

promote genocide and colonial brutality. The ties between colonial

genocide and the Holocaust were obvious, and some of the themes of

collective memory, mourning, and guilt in

Black Box would seem

likely to resonate with the Dutch Jewish community, which was decimated in the

concentration camps. It was a very moving and dark piece of art, and I was

grateful that we came to Amsterdam while it was on display. Some of the charcoal drawings Kentridge incorporated into

Black Box were hung near the installation theater:

Caving to touristy pressure, we bought tickets for a canal tour. People are constantly moving through the canals of

Amsterdam by boat, and they all look like they're having fun, with their

picnic lunches and their wine. I wanted a piece of that fun. And it actually was pretty fun, although less romantic and dreamy, more crowded and

pedagogical. We saw some new parts of the city and got to peek into

the windows of swanky 17th-century houses, a favorite activity of mine.

Amsterdam looks great by boat.

Our experiences with food in Amsterdam were hit-or-miss. The first night, after seeing the Rijksmuseum, we wandered through a dense commercial district with tons of restaurants, all expensive. We settled on a Thai place, which seemed a little cheaper than the rest. We should have left when they refused to serve tap water, trying to get us to cough up 3 euros for a bottle of water or 4 for a pot of tea (!!!), but

instead we stayed and got smacked with an unexpected charge for rice (2.50 euros per bowl, or something similarly ridiculous).

The service was terrible and the food was just okay, and we ended up

feeling pretty miserable about how much money we shelled out for a shitty

meal.

One of the things I'd gotten really excited about in Amsterdam was the number of Surinamese restaurants.

Suriname

is a small South American country, formerly a Dutch colony. Its

unusual demographics arose from overseas workers brought in to work the

valuable plantations and mines in Suriname. Originally, these workers

were African slaves, until the slave trade was abolished in the 1860s

(incidentally, many of these slaves escaped to the jungles of Suriname,

where they developed independent and unique tribal societies and waged

war on the plantations. Plantation owners were forced to make recognize

the rebel slaves' independence and pay them tribute); at this point, the Dutch began importing Javanese and Chinese workers from the Dutch East Indies (now part of Indonesia) and Hindus from the Indian subcontinent. Surinamese cuisine is a

mixture of all of these culinary traditions. Menu items might include

Indonesian

nasi goreng and

gado gado, tempeh sandwiches, Indian

roti with cassava, chop suey, Creole chicken and bean stew, and fried

plantains. Because Surinamese food has such an expansive scope, many

Surinamese restaurants in Amsterdam focus on a particular approach - for

example, Indian- or Javanese-Surinamese. I chose to eat at Kam Yin, a

Chinese/Surinamese place in Amsterdam's Chinatown, abutting the Red

Light District. The food was cheap and delicious.

|

| This roti was beyond belief |

It's hard to see a city in three days, even though I think we used our time well. I'm sure we're going to feel this way about everywhere we go in Europe. I'm really sorry we missed the

world's oldest botanical gardens and the

Tropical Museum, both of which look awesome.

|

| Hortus Botanicus Amsterdam |

|

| Tropenmuseum |

I'd also like to see the Dapper Market, a large open-air pedestrian bazaar where goods ranging from fresh fruit to bike parts are sold out of tents and carts, and the food vendors are supposed to be great. We walked through the Dapper Market area in the evening, after the market had closed up. It's primarily an African and South American neighborhood, with many shops catering to the Netherlands' immigrant communities.

On Tuesday, we were up and checked out of our hostel early, and walked with

our packs to the natural foods market, in preparation for the day of

travel which would take us to our first WWOOFing farm in the

Noordoostpolder, where I am presently writing. There's a lot to say

about our experiences at the farm, which will have to wait for another

day.

Without much context for comparison, I find it hard to judge Amsterdam's

merits relative to other European cities. Certainly, it conforms more

to the American idea of Europe than Reykjavik or Edinburgh, but that's

unsurprising. There were things I liked and things I didn't (bros,

mostly), and many things that struck me as unique that probably aren't,

and maybe I should hold final judgment until I've become inured to the

novelty of pre-18th-century architecture and funny accents.