We ended up in Sarajevo entirely by accident. We had tried to take a series of trains from Budapest to Ploče, Croatia, where we'd proceed by bus to Dubrovnik, the ancient crown jewel of the Adriatic. Yet, we found ourselves, instead, in a city best known for ethnic cleansing. Travel is that way, sometimes.

Our overnight train took us from Budapest to Zagreb (a place we would later spend some actual time), then to Sarajevo, where we were meant to catch an early-morning connection to Ploče. The train was standing still when the 6 AM alarm went off, informing us that we should be reaching Sarajevo in a few minutes. I don't know why or how long we were stopped, and they made no announcement about it. We didn't make it to Sarajevo for another two hours, long after our connection had left.

There are only two trains from Sarajevo to Ploče. The evening train is substantially longer than our missed connection, and because of the way overnight travel is calculated for the purposes of our Eurail passes, it would have counted as two "travel days" out of our 15 total. So, our only viable option was to stay in Sarajevo for the night and catch the train the next morning.

The early hour of our awakening, our frustration about the delay and associated expense of having to book a hostel, the frequent interruption of our slumber by conductors and passport-checking apparatchiks, and my brain's violent demands for its customary morning caffeine bath all contributed to a contentious and irritable attitude Jenna and I shared. We shared it quite volubly, in fact, with each other that morning. That's another thing about travel.

Given that we had no expectations for Sarajevo, it could do nothing but exceed them. It's a strange city geographically. It's very long and narrow a shape necessitated by the hills which surround it. Sarajevo's most noticeable feature was also its downfall. In 1992, Serbian forces used the city's natural barriers to blockade and lay siege to Sarajevo, positioning artillery, snipers, and tanks on its encircling verdant slopes. Wikipedia describes the unceasing, indiscriminate shelling of the siege as "urbicide." For nearly four years, Sarajevo was under daily fire, cut off from supplies, and without utilities. 35,000 buildings were destroyed entirely; almost none were unscathed. Tens of thousands of people were killed.

It was a bracing thought for me, sitting in a mediocre bar/café that morning, that most of the people around me were old enough to remember searching the rubble for firewood amidst sniper fire. Perhaps more disturbing was the realization that a few of the somber, middle-aged men around me may have been on the hills, raining hell down on the streets below.

The reasons behind the Yugoslav Wars are the kind of ethnic and religious conflicts that make sense only to those embroiled in them. The self-evident wrongness of one's neighbor is usually lost on those at a distance from the situation. What's frightening about the Balkans is that it's very difficult to ignore their relevance to us, as Americans. It's easy to classify ethnic war as a problem of the Other when it breaks out in Africa, or Central Asia, or elsewhere in the "third world." After all, we reason, the Hutus and Tutsis aren't educated like we are. Their tribal loyalties haven't been dissolved by their entry into the modern, globalized capitalist marketplace, where we find equality in our status as consumers. They lack the historical consciousness we've obtained by ex post facto analysis of the genocidal campaigns of Hitler, Stalin, and Pol Pot.

But in the former Yugoslavian nations, we have no such explanations at our disposal. The people of the Balkans were educated, cultured, and prosperous (much more than any other Communist bloc country). They're pretty much indistinguishable from any other white European ethnic group. For decades, they coexisted, with only occasional rumbles of discontent, as part of the same nation. Nor can we build a comfortable narrative about Communist religious repression leading to an eventual explosive release of religious tension. To the contrary, religious practice was unrestricted in Yugoslavia. In short, it's hard to see them as the Other.

Sarajevo is allegedly the only city in Europe that boasts a synagogue, Orthodox church, Catholic cathedral, and a mosque in the same neighborhood (although I suspect this tourist-brochure claim rests heavily on how strictly one defines a neighborhood). It was the Jerusalem of the West. Then it all fell apart, in what must have felt like a slowly-unfolding nightmare to the people caught in the midst of the unspeakable horror of the war.

It is more disturbing when mass killing takes place in an industrialized, rather than a subsistence-agricultural, society, because the killing itself is industrialized. The unifying feature of modern genocide is the prison camp: a place existing as an exception to ordinary law, where inmates become, to use Giorgio Agamben's term, homines sacri, their bodies the locus of state power. The prison camp strips its inhabitants of will and identity. Like animals in a factory farm, they become bodies for processing.

The paradigm always seems stable before its collapse into a new form. The nature of ideology is its apparent completeness and transparency: ideology presents itself as the only natural conclusion of rational thought, existing therefore beyond the merely cultural or temporary. To envision alternatives to the prevailing worldview is nearly impossible, because we lack the terms in which to articulate them. Like a spinning top, a dominant ideology will seem quite likely to continue forever until the moment it develops a wobble; then it appears impossible that we couldn't have foreseen its toppling.

In Hegel's view of history (and, through Hegel, Marx), world events and paradigm shifts take place because of historical necessity. History has a sort of inexorable, slow movement, that, like plate tectonics, occasionally leads to ground-breaking sudden shifts that rearrange the terrains of power. The French Revolution, for example, was a radical event that obliterated an existing ideology, but laid the groundwork for a new hegemony, against which newer revolutionary movements have struggled. But unlike plate tectonics, in this view, history progresses towards an endpoint, creating ever better, more perfect forms of governance and relationships of power. History chooses its own path.

I don't know if I completely agree, but to think that we're entirely in charge of the course of history is a mistake. One thing that seems true is that history chooses its own heroes: the people who initiate a conceptual revolution. They doesn't have to be innovators, or great intellects. Often, some unlikely proponent of an old, unpopular concept, will find that suddenly, people are listening to him. The value of education and historical consciousness is to help ensure that when a sea change of public opinion occurs, history chooses a hero like Gandhi, and not one like Hitler.

All it takes is some small historical oddity to turn the full force of the state apparatuses of systematic violence against a vulnerable minority. As much as we believe that totalitarianism, theocracy, or racial or religious "cleansing" could never happen in the U.S. or Western Europe, all it would take is a charismatic populist leader to simplistically appeal to the fears of the populace, in that hard-to-identify moment of ideological wobble.

We spent much of the day walking through the city, trying to find lunch and a place to stay. We did both. We ate at Karuzo, a restaurant downtown recommended on HappyCow. The place is decorated with a nautical theme, but not in a bullshit crab-shack kind of way. Being in Karuzo is like stepping into an old-time wooden ship's cabin.

The restaurant serves fish, but no chicken or "red meat," and much of the menu is vegan. The food was delicious. It would have impressed meat-eaters with its convincingly rich sauces and meaty seitan, but didn't fall into the trap I complained about in my last post, of trying so hard to imitate omnivore dishes that it loses focus on nuanced flavor. Saša, the owner-operator, is an eminently capable cook and an iconoclast in an area whose regional cuisine is defined by meat.

We had sent out some CouchSurfing requests, but there weren't many hosts in the city, and it was very short notice. No one got back to us. We booked the cheapest hostel in the downtown area. Locating it was difficult, and when we finally found it, no one was there to let us in. It was probably 45 minutes before someone came - I was actually fetching Jenna to go to another hostel, having left her with the packs so I could find a free wireless internet connection to look up the phone numbers of other places to stay. It was nondescript but clean, and since the rooms had only two beds in each, we had a room to ourselves.

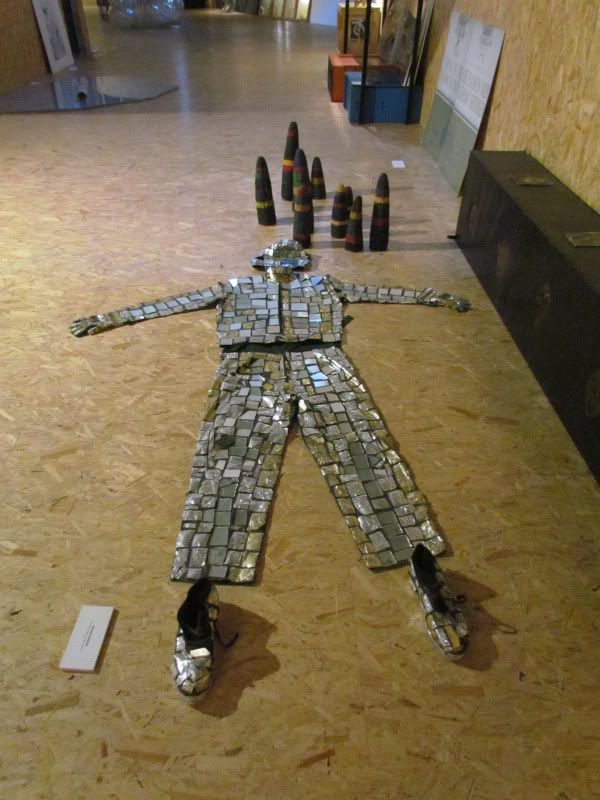

It was now mid-afternoon. Most of the museums closed at 4 or 5. We decided to try the Ars Aevi contemporary art display, which was open late. It was tucked away in an ugly sports arena/civic complex.

The display is a semi-permanent traveling exhibition of contemporary art. It was free, which was nice. It was a very strange place. The art was propped against plywood shipping crates, or set atop planks. I didn't like most of it, my appreciation for art after 1930 being mostly academic. I understand that there was an important point to asking questions about what constitutes art, how we define art, what the appropriate subject matter of art is - but now that those questions have been asked, the edge seems a bit dulled.

|

| Mustafa Skopljak, Light and Dark |

|

| Wow, what a complex yet controversial topical commentary. Are you freaking out? |

|

| Joseph Beuys, 100 Bottiglie di Olio F.I.U. - Difesa della Natural. This one was kind of cool, admittedly |

It's like our culture's high arts are just milling around the ruins of a formerly relevant tradition and have no concept of how to move forward beyond or outside that tradition, which has been declared finished for the better part of a century now. There's only so far you can push the meta-art envelope. Or else maybe these artists are doing something else and I'm missing the point completely.

Anyway, it was a pretty small museum. We walked through the old city, which was lovely in the late evening.

There are a huge number of souvenir shops, more even than Prague, but they sell more artisan, high-end stuff. There were some gorgeous copper Turkish coffee sets, beautiful glass-beaded lamps, and filigree jewelry. The cafés looked swanky and modern.

The prevalence of Islam surprised me at first. The Bosnian ethnic group is traditionally Muslim, a fact I was unaware of before our visit to Sarajevo prompted me to do some research on the Yugoslav Wars. The city has many mosques, and the callers on the minarets can be heard (thanks to electronic amplification) from almost any point in Sarajevo. Their voices put us to bed, and were audible again when we awoke - very early - for the train to Ploče.

We hadn't planned on being in Sarajevo at all, but I'm glad we had the layover. The city still walks with a limp from the protracted siege. It's more than the bullet holes and shrapnel pits in the city's walls. Most tourists feel about Sarajevo as I did: it's a war-torn place of sorrow and solemnity. It is and it isn't. Given the extent and recency of the damage, it's perhaps surprising that Sarajevo goes about its business as casually as it does. There are open-air cafés and nightclubs and well-dressed businessmen and kebab stalls and all the other expected signifiers of a prosperous small city. But I don't think I'm imagining a collective, secret horror and shock lingering from the city's acquaintance with the intensive, yet indiscriminate death that characterized the Balkan conflicts, a legacy of prison camps, massacres, and organized rape that won't dissipate into the fog of time for many, many years.

Being in Sarajevo gave me an important point of comparison for the places we saw in Croatia, another combatant in the Yugoslav Wars, and caused me to learn more and reflect on the history of this troubled corner of Europe.

Great post, but it is somewhat unfortunate that you did not appreciate the beauty and cosmopolitan aspect of the city as much as it has to offer. I would not describe Sarajevo as war torn considering how much of the city has been rebuilt, nor would I say its a city of sorrow - it is quiet dynamic and bustling city with the most dynamic cafe culture I have encountered anywhere in Europe, certainly in Eastern Europe.

ReplyDelete