Aram writing here. The easiest way to get from Prague to Česky Krumlov ("Č" makes a "ch" sound, the "Š," a "sh") seemed to be by bus. We tried to catch an 11 AM bus, but were surprised to find that the 11 AM and 1 PM buses were both full. We had to book tickets for 2:30. The website made it seem so easy. Learning that the internet can lie is a painful lesson. So much for walking that day; clearly, we would have to wing it and find someplace to stay or camp very close to Česky Krumlov.

There's very little practical information on the internet about backpacking in Šumava Park. There are just general references to a plethora of trails criss-crossing the area. We were heading to Česky Krumlov with no idea of where we would end up, or how we'd get to Vienna on the 19th. Because of our extra day in Prague, we were leaving on the 17th, and because of our lack of foresight in booking bus tickets in advance, we wouldn't be getting into Česky Krumlov until about 5 PM. We were watching our plans for an extended, picturesque village-to-village hike evaporate into, most likely, a circular day walk to and from Česky Krumlov.

While waiting for the bus, a young Israeli couple with a baby asked us for information about how to buy bus tickets. They were also heading to Česky Krumlov. We struck up conversation with them, and they told us we could stay with them if we made it to Israel. It was a generous offer, and I hope we can take them up on it.

Jenna writing now:

We walked from the bus station in Česky Krumlov to the center of the small city, hoping to figure out our accommodations for the night.

Back to Aram. We woke up the next morning excited to rent a canoe. After some technical and linguistic difficulties - aren't there always? - we determined where we needed to go. I'm still not totally sure what the mix-up amounted to, but I think we ended up staying in a completely different camp from the one I'd phoned the night before. Anyway, we walked less than a half-mile down the road to the next camp, where we could rent a canoe. Unfortunately, it was prohibitively expensive. We would've been set back something like $20 for a one-hour canoe ride to Česky Krumlov. Forget going south, into Šumava - it wasn't possible at any price.

Disappointed, we walked toward Česky Krumlov, trying other boat rental sites, each more expensive than the last. In town, we harnessed a café/bar's WiFi and planned.

As things then stood, we were supposed to catch a bus or train to Vienna the next day. Our canoeing fantasy having been stymied by its high cost, we had now wasted most of the one full day we'd committed to outdoor exploration before plunging again into a steady stream of urban experiences. We shrugged our shoulders and e-mailed CouchSurfing hosts in Vienna and Budapest, our next stops.

Doing our best to salvage the remains of the day, we wandered the picture-perfect streets of Česky Krumlov, joining the masses of German, Austrian, Japanese, British, American, and Australian tourists snapping photos, dressed in khaki shorts and PGA Tour hats. Bored daughters busied themselves over Bedazzled cell phones; teenage boys leered. I wondered how this city came to its present state, preserved as if in amber. It must be governed by strict building codes. There are a few ordinary high-rise apartment blocks on the outskirts, but within the UNESCO World Heritage central zone, no building looks remotely contemporary. Like the plaster dinosaur skeletons in a natural history museum, Česky Krumlov is an artificial and dramatic educational ruse illustrating the past through inexact supposition, as an illusory whole. And like those plaster bones, Česky Krumlov is devoid of life: the historical district is all hostels, pensions (the locally preferred term for a guest house, ranging in formality from a miniature hotel down to a spare bedroom in someone's home), restaurants, souvenir shops, and galleries. The workers live outside of town. Visiting Česky Krumlov in 1928, say, would have been a unique, private exhilaration, like stumbling upon a bear in the wild. Today, it is like looking at one in a cage.

Of course, caging our bears isn't an exclusively modern foible, as we saw literally manifested in the moat of Česky Krumlov's enormous castle. Therein reside two painfully bored-looking brown bears, probably the only representatives of their species in the region (the last wild bear in Šumava was shot in 1856).

The castle was a seat of the noble Rosenberg family, parts of it dating from the mid-13th century. It's extremely well-preserved, or, more probably, well-restored. We weren't willing to pay for entrance to the interior, but advertising photos in the courtyard promised lavish period appointments within. The courtyard itself was nothing to snort at, though, and provided aerial views of the town center.

We walked through the formal gardens to some manner of probably-18th-century outbuilding, which was being actively refurbished, and a lily-choked pond.

I could see figures walking dirt paths in the fields just beyond the castle walls. I felt a little frustrated. Those paths were probably the ones we'd planned on hiking, but it just wasn't going to work out, obviously. I felt constrained by the itinerary we'd laid out.

We took an intentionally meandering route back to Nové Spoli. On its southern outskirts, Česky Krumlov has many small houses terraced into the hillside, girded by rustic and ancient rock retaining walls. The hillsides are so steep that the residents employ cart-and-pulley apparatuses to bring groceries up to the houses. I wanted to see these houses closer up, so we walked the twisting, steep, narrow streets up the hillside.

I reflected on the fact that most of these retaining walls, drainage chutes, and graded streets were the products of amateur engineers, probably untrained formally, who relied on intellect, common sense, and, in no small measure, trial and error to construct these intricate systems. There weren't computers or calculators to help plan these terraces, nor even mechanized digging equipment. This also begs another question: why were people so eager to pack themselves together like matches in a box? The oldest known city, Çatal Höyük in modern Turkey, is a dense mass of human habitation dating back some 8,000 years. It's so dense, in fact, that to access some of the homes, inhabitants would have had to clamber over their neighbors' rooftops to slide in. The strange thing is that Çatal Höyük stands in the middle of a plain of perfectly good building area. This sardine-can design would have probably been detrimental defensively; it seems to serve only a psychological purpose. People will go to great pains, even to hewing stone by hand from the hillside, to be in proximity to others.

It was a pretty view from the top of the hill. On the way back down, I hoisted Jenna up in my arms so we could snatch some juicy apples from a tree hanging over somebody's wall. They were delicious.

We found some discarded wood on the side of the road, and carried it back to our campsite to burn. The sun was just setting. We took advantage of its final rays to swim in the river at our camp.

|

| Dat tan line |

As the sun set, it got very cold, and I was glad we'd built a fire. The difference in temperature between day and night is great in this part of the world.

Jenna writing here:

As we looked at the mysterious paths leading into the forest behind the castle, we were both feeling a little bitter and frustrated. None of our plans had worked out up until that point. Getting information on how to enter and find hiking trails in Šumava National Park had been a bust, canoe rental hadn't worked out (though for that we had only our unpreparedness to part with the hefty fee to blame), and now we had to go to Vienna the next day, feeling as though we had done and seen nothing that we had really wanted to.

It took a while of griping about this before the thought occurred to both of us - why did we "have" to go to Vienna? Of course it was supposed to be a beautiful city, but if it meant the end to our time in the Czech Republic before we were satisfied, why go? I think we hadn't really felt the freedom of our trip until this moment. We had made plans and stuck to them, mostly because they matched up with what we wanted to do anyway, and so thus far we hadn't deviated from our schedule at all, save for the one extra day in Prague. It was liberating to realize that we didn't have to do anything in particular. We wanted more time in the Czech Republic to do some hiking; we could have it.

That night we cancelled our CouchSurfing requests in Vienna and started making the first of what would become many versions of a plan for our hiking days. We first planned to walk the next day from Český Krumlov to Horní Plana, a town which lay in the southwest of the country on Lake Lipno. The day after that we would walk south to Frymburk, and then end the following day in Vyšší Brod, in the southernmost part of the country. We hadn't looked at any hiking trails in particular yet, but we had looked at a map of the country and knew that these hikes at least appeared to be manageable daily distances for us, and would also provide some interesting walking.

When we woke up at 6:00 the next morning, intending to get an early start on our day to Horní Plana, it was pouring. It continued to pour all morning. We have rain jackets and waterproof pack covers for emergencies, but a long, miserable, and wet day was not what we wanted for ourselves. We decided to stay one more night at our campsite in Nové Spoli and hope the weather would improve the next day. We did eventually manage to drag ourselves out of our tent and walk into Český Krumlov for the day. We got some coffee at a pleasant little fair trade shop and then decided to visit the Egon Schiele Center, which we had seen a sign for on our first day.

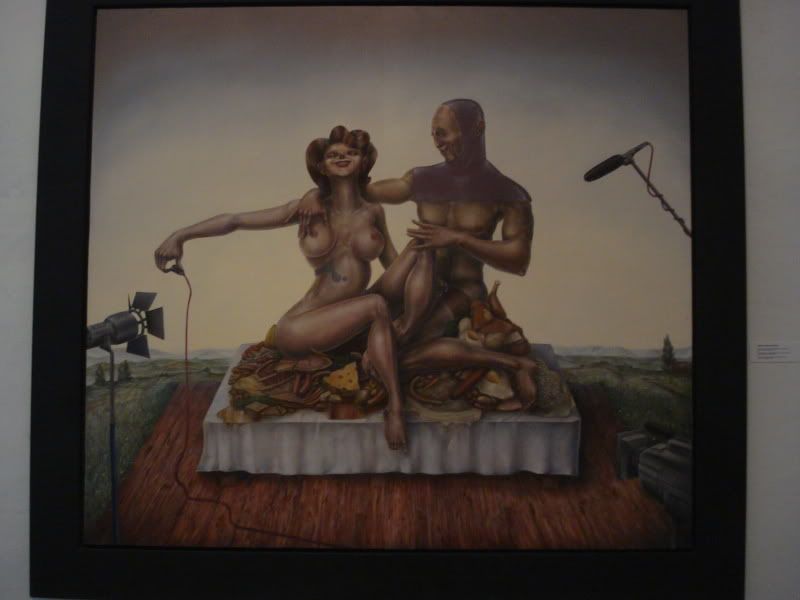

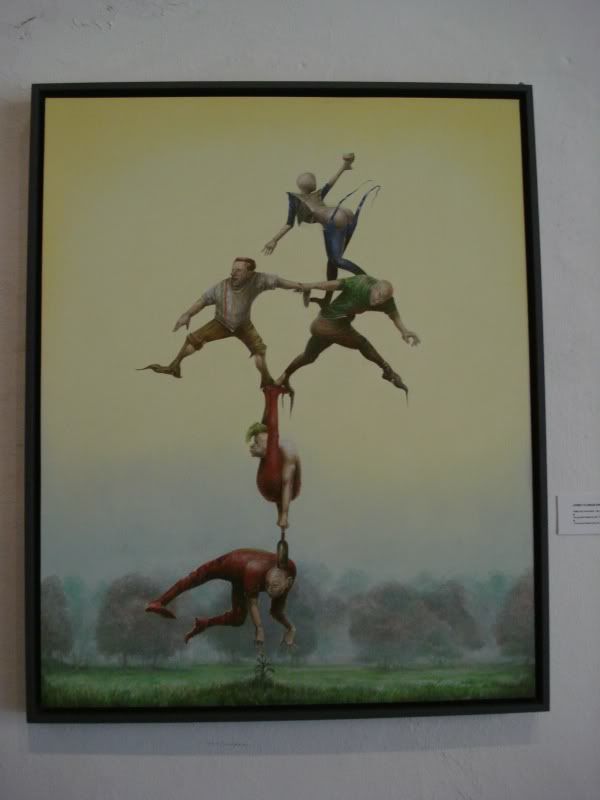

The Egon Schiele Center is rather boldly named so. The center boasts one room of photographs and historical information about the artist, and one small room of mere copies of a few Schiele paintings. Aram and I found this pretty comical, however it didn't stop us from enjoying the rest of the center outside of this "collection." There were several other interesting exhibits. There were some paintings by Florian Krichbaum, whose style has a certain caricature quality to it. His paintings seemed mostly concerned with excess, a lot of times represented by food. His work was often comical, but pretty dark.

|

| Hit Hard, Generation Big Brother |

|

| The Great Balancing Act |

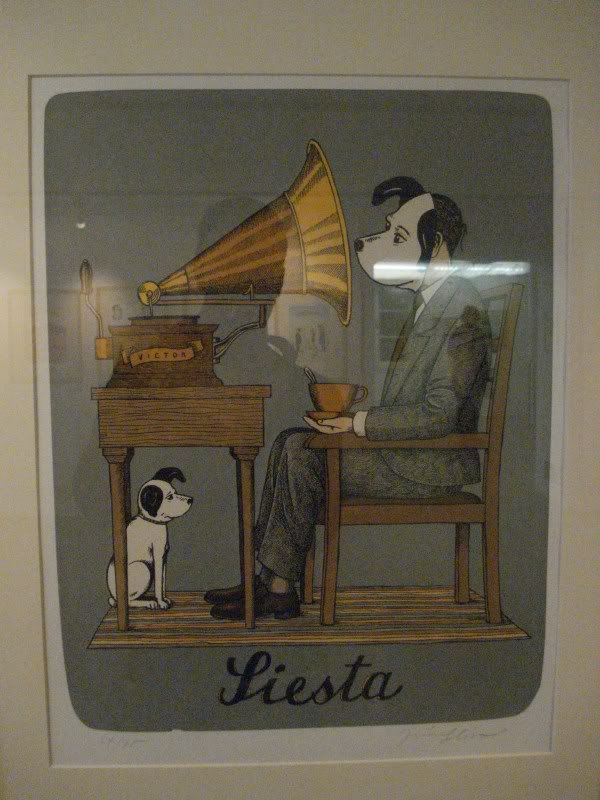

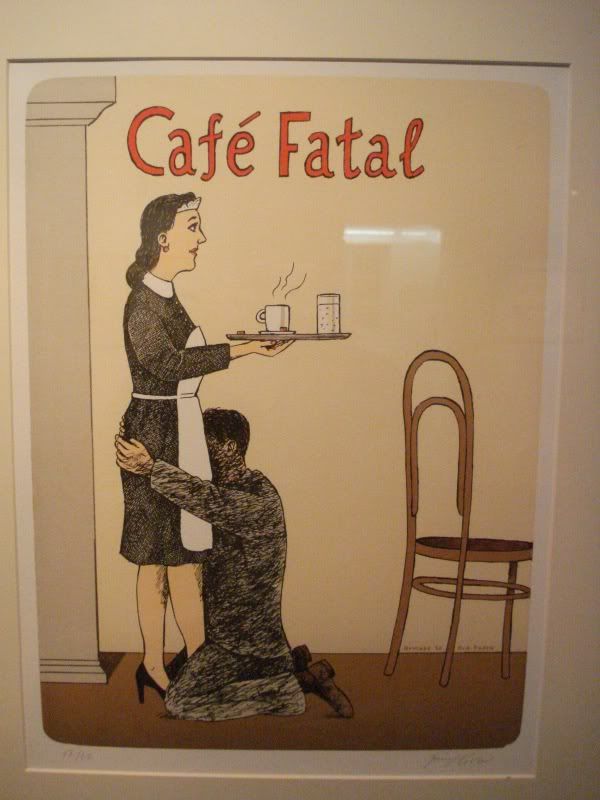

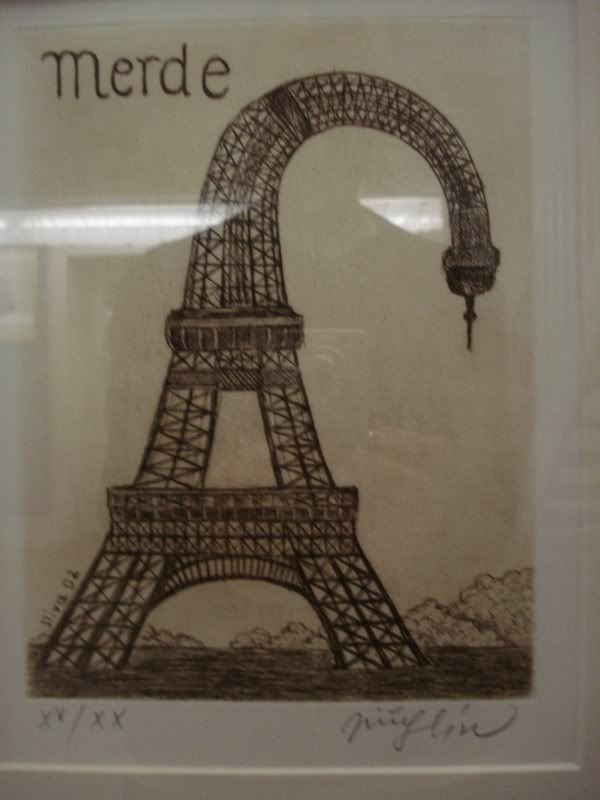

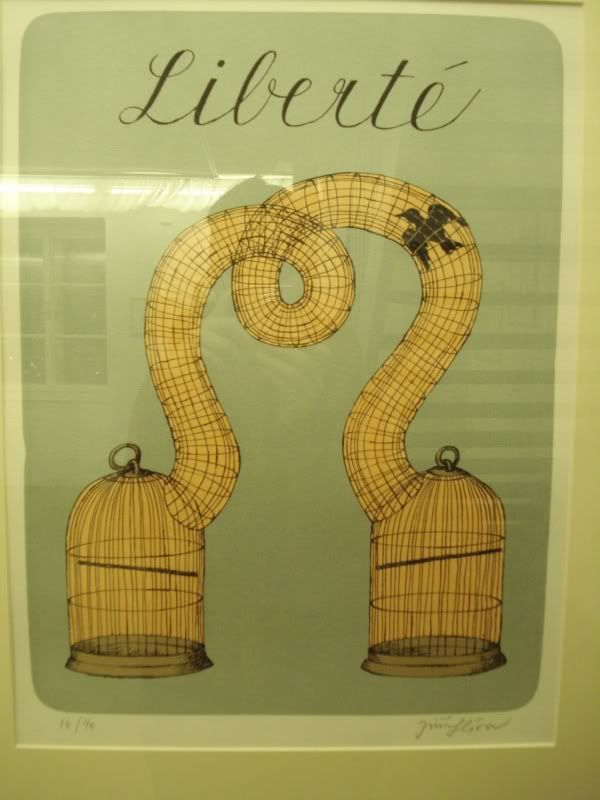

There was also an exhibit by Jiri Sliva, whose work is a mix of prints and pen-and-ink drawings. His pieces focused on a few major categories - coffee, alcohol, etc. - and ranged from being light and amusing to quite dark and disturbing. I liked this part of the center best and will probably search for some Sliva prints to have for myself, at least reproductions. The museum was actually selling some of his original drawings and prints, which was cool.

Aram: Sliva was my favorite artist on display at the Schiele Center. His prints and drawings reminded me of a combination of the work of Edward Gorey and Raymond Pettibon: the former because of the style of the pen-and-ink rendering; the latter in the unsettling, sometimes sexually suggestive subject matter concealed within a cheery, cartoon-like surface.

|

| Siesta |

|

| Café Fatal |

|

| Coffee Station |

|

| Merde |

|

| Liberté |

|

| Holy Family |

Jenna writing again. There were also several large spaces devoted to an exhibit of the work of Gerald Scharf (wikipedia seems to spell his last name Scarfe, while most other places seem to insist it is the former; I have no clue which is correct, maybe he goes by both?) who seems best known for his political cartoon work and his work doing concept art and animation for Pink Floyd's "The Wall." There were no photos allowed, but suffice to say that a lot of Scharf's work is dark - very dark, and often sexual in nature. It's very strange, then, to know that Scharf was also responsible for the concept art and design behind Disney's "Hercules" movie. Who was the mind being that decision? It's not that Scharf's design work isn't good, but what about his drawings of Tony Blair with his head stuck graphically up George Bush's ass just screamed "children's movie concept art" to Disney?

We got yet more coffee at another cafe after the museum, perhaps even more charming than our first one that morning.

Then we visited the information center and picked out a hiking map of the area in preparation for our walk the following day. We headed back to our campsite later that evening. Our plans were still fluctuating. Having looked at the map, it was really difficult to determine where to pick up a trail to get us to Horní Plana the next day. We were also unsure if it were actually doable in a day's walk. Based on roads, Google Maps had put the walk time at only 5 hours, but we realized that this was irrelevant because the trail we were trying to take meandered quite a lot. We went to bed hoping we could wake up early and figure it out easily in the morning.

Unfortunately, the events of the next day had already been well predicted by our difficulties pinpointing a specific starting point for our hike. We were unable to find a trail to Horní Plana with a pickup point near Český Krumlov on the map. We argued about which route to take, and we were both frustrated that our seemingly simple plans to hike leisurely through forest paths was appearing to be next to impossible. We got a very late start, and then spent over an hour wandering around Český Krumlov with our packs, trying to find a trail head - any trail head. Eventually we did find a red-blazed trail, which according to our map just circled Český Krumlov, but it looked like it would connect us to European long-distance trail E10, blazed in blue, which we could follow south. Because this was the only clear option we had, we changed our plans accordingly, deciding to skip Horní Plana and just follow the E10 south as far as we could get that day. We hoped to make it to Světlik, where it appeared there was a campsite (wild camping is strictly forbidden and enforced in the Czech Republic. We would have done it if necessary of course, but were hoping to avoid it if we could, as neither of us were too keen on the possibility of being woken up at an early hour by a disgruntled local or forest ranger). The following day we would hopefully continue south to Frymburk, and then to Vyšší Brod as planned.

It took forever to even find the E10 trail. We had wandered maybe 4km on the red-blazed trail and offshooting paths, but when we finally did see the blue blazes it was quite a joy.

The blazes were nonsensical and the path hard to follow, but the walk through the forest and countryside was beautiful, and were were both happy to have a destination.

There were numerous shrines and trailside crosses along the path.

However, we hadn't started on the E10 until the afternoon, and from the point we'd joined the trail it was over 12km to Světlik. Around 4PM the trail passed through a very small village called Slavkov.

We toyed with the idea of staying there for the night, but there was no campsite or even viable wild camping place in sight, and the only pension in the two-road town was abandoned. With no other options, we decided to press on to Světlik, and hoped we could make it there before dark.

With about 5km to go, we were walking along a dirt road that cut through the lovely forest and neighboring farms. Suddenly a car pulled up next to us driven by a young woman, maybe a few years older than us. She asked us something in German (we were close to the Austrian border, and as we would come to find out, German was a spoken by enough people to be a fairly reliable mode of communication) which we took to be a question of whether we wanted a ride somewhere. We said we were going to Světlik, and she motioned for us to get in. "Drei kilometers,"she explained, "äber nicht Světlik." We nodded and I assured her in my pitiful German that 3km was "Sehr, sehr gut, danke!" We drove in silence for a short while and she let us out about 2km from Světlik. We thanked her profusely - the ride had assured that we would reach our campsite long before dark - and walked on. Just before we reached town, we realized that in our awkward attempts to wrestle our giant backpacks out of her car, we had left the map on the seat. Aram wants me to specify here that it was him who left the map, but really it could have happened to anyone.

It wasn't good, but there was nothing to be done about it at that point, and for the time being we knew more or less where we were going, so we continued into town, hoping we'd be able to replace the map in the morning. Luckily Aram had remembered where in town the campsite was supposed to be, so we headed in that direction. I was having trouble imagining what a campsite in the middle of town could look like, but pretty soon my questions were answered when a sign saying "kemp" led us to someone's private home on a hill, with a list of camping prices tacked up on the fence. As we approached, we heard what sounded like a giant, ferocious dog barking at the fence. On the plus side, the prices were fantastic. We rang the bell.

The man who answered the door spoke no English and seemed to be a little simple as well, but he was kind and managed to communicate that it was fine for us to stay, but that payment and other such arrangements would have to wait until his family returned home, which would be soon. When he opened the gate for us, the dog, looking part wolf and still barking wildly, came running at us. We held out our arms and let her sniff us and check us out. As soon as she had determined that we were acceptable guests, she morphed at once into an absolute sweetheart, rolling submissively on her back to let us scratch her belly, and running happily all over the property.

The man showed us the yard and the camping facilities. There were small caravans which we could stay in for more money, but we declined. We chose a nice spot in the corner of the lawn and started setting up our tent. There were private bathrooms for campers (of which we were clearly the only ones, it being so late in the season), equipped with hot showers at no extra cost, and even a clothesline and pins to hang wet things. The yard was well-kept and overlooked a field and the town. The dog was kissing our fingers. In short, though it was weird to be camping in a stranger's backyard, it was quite idyllic.

When the man's parents returned home, we paid them (about 5 dollars) and the father started puttering about tending to us, setting up a plastic table and chairs, showing us the bathrooms again, asking us if we needed anything. We cooked a giant meal of lentils, rice, mushrooms, garlic, lemon juice, curry powder, and salt, which we were glad to have (we had finally bought some that morning before leaving) and devoured it as the sun set.

It was especially freezing that night - when we awoke in the morning, our rain fly was covered in a thin layer of ice. Despite our long day the day before, neither of us had slept well again. We ate and packed up, thanked our hosts, and were on our way.

We didn't see anywhere obvious to buy a map, and we didn't want to waste too much time looking. We saw a sign saying "Frymburk 11km E10," and so we decided to just keep following the trail until we got there. We remembered from looking at our sadly-lost map that the E10 pretty much just headed south through the Czech Republic, which was our intended direction, so this information combined with the sign in Světlik left us feeling confident that as long as we followed the E10's blue blazes, elusive as they sometimes were, we would reach Frymburk eventually.

We set out for our relatively short and easy hike in high spirits. We passed through some tiny, wonderfully charming little villages, barely even a street each, and also through some more tall and cool wooded areas.

Many times we got lost and turned around trying to follow the trail, which continued to be really badly marked. We passed by someone's summer home, and stood for awhile taking pictures of the herd of deer hanging out on the property. Thankfully, there were no people crouched in the hunters' perches built on several spaces on the lawn. We weren't sure if the deer were trapped in there or not.

We came to a point in the trail where the way was split. One sign indicated the continuation of the E10, which we were following to Frymburk. Another was a bike path, and it said "Frymburk 14km." The E10 sign made no mention of Frymburk. Instead it listed various other places, including Horní Plana. We had a conversation about what to do, but eventually decided to stick to our plan and just keep following the blue-blazed trail.

Around 1PM, we wandered into Černá v Pošumaví and decided to check out a public map posted of the area. To our great surprise, we were not any further south - instead, we had walked northwest, and were indeed headed in the direction of Horní Plana. We had no idea what had happened, but decided that as long as we were walking in the wrong direction, we might as well change our plans completely, and just try to make it to Horní Plana that same day. As it turns out, the E10 continues south, and another trail blazed in the exact same marking heads west to Horní Plana. This was the path we had inadvertently followed. We crossed Lake Lipno on the way.

It was a long day of walking (about 19km total), but we made it to Horní Plana by early evening, and found a campsite for the night on Lake Lipno, which was very pleasant. We hadn't yet decided our plans for the next day, though we knew we had to make it to Budapest eventually.

Aram again. We awoke to a dreary, drizzly day. By mid-morning, we had packed our campsite up. According to the Eurail website, there was only one train daily from Horní Plana to Budapest, and it would be a long ride. So, we decided to grant ourselves our reward night in a pension in Vyšší Brod, the town we'd originally designated as our endpoint. Vyšší Brod is roughly the same size as Horní Plana, but more accessible by train. We were able to catch a bus to Vyšší Brod via Česky Krumlov - reversing, in a span of half an hour, the distance we'd walked in two days.

Vyšší Brod is an attractive village, if not superlatively so, built around a long central street, divided by a stretch of park. Along this street, we inquired at four or five pensions. They mostly had bars or restaurants on the first floor with rooms above. One had an attractive café at ground level, and quoted us the best price - 750 crowns, or about $35.

In retrospect, I'm embarrassed for having comparison-shopped. Any other pension in Vyšší Brod should feel ashamed for any guest they draw away from the Alpenrose/Alpska Ruze pension. It's run by a white-haired, tidily-mustached gentleman who goes by the unlikely name of Jimmy. The pension and café are clearly his passion. At this time of year, past the peak of Lake Lipno's high season, it's a one-man operation. Jimmy gets up at the crack of dawn to bake apple strudel and prepare the shop for opening. The café is full of a lifetime's accumulation of treasures: high-quality art reproductions, Oriental rugs, antique furniture, crystal chandeliers, jewelry, and cut glass. Some of these things are for sale, but most are just decorative.

We were in the habit of trying to negotiate in a broken combination of German and English. Because of our proximity to the Austrian border, people in this part of the Czech Republic understand German better than English. Unfortunately, neither of us really speak German. After asking for, "Ein zimmer, ein nacht, für zwie people, mit nichts breakfasts, bitte," we pantomimed that we'd like to see the room. Jimmy took us upstairs and unlocked the door to a room substantially larger than some of the apartments I've lived in. Our jaws dropped. "It's okay?" he asked.

"Yes," we said in stunned unison.

"Sehr gut," added Jenna.

"Okay," said Jimmy. "You can put your things down. I'm going to fill out some paperwork downstairs. Take your time, and come down with your passports when you're ready."

Jimmy, clearly, spoke nearly perfect English, and I felt a little sheepish for our confused, slapdash Anglo-Teutonic improvisations.

Our room had an enormous, comfortable bed, mini-fridge, a glassed-in balcony, and a full-sized bath.

There were a hundred nice touches, from the weird art on the walls, to the beautiful water glasses on a silver tray, to the little curtain concealing the exposed plumbing beneath the sink. I've rarely been in such a spacious, comfortable, and attractive room. I'm certain the more expensive pensions wouldn't have come close to being as wonderful.

After a just-okay (but very cheap) meal of pizza around the corner (chosen for their free WiFi), we came back to the café and had a cup of coffee while chatting with Jimmy. He adopts a squint while listening, which gives him a stern and skeptical appearance, but when he speaks, there's no judgment in his words. He is a gentle, kind, hardworking man who loves what he does.

"It's not very busy now, no. But I like it a little quieter," he said. "There's more money when it's busy, sure, but when you're old, you don't need much money. I don't buy an iPhone, or a new car every two years, so why do I need money for?"

It's inspiring to speak with someone who so clearly has his life figured out. He seemed extremely content, turning the enormous amount of work required to run his pension into the structure and joy of his life. We filled out our identification information for Jimmy.

"Do you know Face Book?" he asked abruptly.

"Yeah," I said.

"Do you like it?

Jenna and I debated a bit between ourselves, but stated that basically, we did.

"Maybe we can be friends?" he asked. "I don't know too much about it. My assistant in the busy season is in her twenties. She made a Face Book page for the café - for guests."

We were both very happy to accept. Jimmy was overwhelmingly nice to us. He charged us a pittance for the coffees and Jenna's reportedly exquisite apple strudel. The evening was relaxing and wonderful. We both bathed, and Jenna did laundry in the sink. The bed felt indescribably welcoming after days of frigid camping.

We reluctantly left the warmth of our room and hefted our packs downstairs the next morning for breakfast. I ordered oatmeal with some fruit; Jenna had eggs and cheese. Both turned out to be sumptuous beyond expectations. Once again, we were significantly undercharged by Jimmy, who wouldn't accept more.

I could not have imagined a better stay. Jimmy was so kind, friendly, and generous. It was our pleasure to stay with him. If you ever have the chance to visit the Czech Republic, make it your business to stay with Svát'a in Prague, and make a detour to Vyšší Brod to visit the Alpenrose.

The spontaneous attitude that we began to adopt in Šumava has been very important to our time in Europe. It's injected new enthusiasm for what we're doing here. Recognizing that we can keep any schedule we want was very freeing, and while we adhered pretty steadily to an itinerary for the first half of our time abroad, we've already been playing much more fast-and-loose with our plans for the second. This sense of freedom would only be reinforced during our strange time in our next stop, Budapest. Stay tuned, readers.

Leave a Reply