Our arrival in Budapest perhaps prejudiced me unfairly. For one, we have usually gotten into a city before dark; night had just fallen as we pulled into Budapest. Additionally, our point of disembarkment has thus far been in the well-lit central zone of serious-looking stone buildings that we are now quite used to in Europe (Reykjavik was the exception on both counts). Budapest's Keleti Station doesn't exactly put the city's best foot forward. We exited the terminal to find ourselves in a roiling mass of illegal cab operators, drunks, Turkish hucksters, mendicants, and skinhead soccer hooligans. We called our CouchSurfing host, a young guy named Kjartan, to get directions, but couldn't immediately find the street we were supposed to set out on.

So, our first impression of Budapest was not that of the lovely, divided jewel of the Danube, but rather, the seedy, dirty, and ramshackle interior of Pest. Dog shit is a major feature, as are sex shops, and the homeless are numerous (in other cities, we saw beggars, but most earn enough by day to stay in a hostel or shelter, removing themselves from the streets thereby. In Budapest, as in the U.S., the homeless sleep on the sidewalk). Budapest looked gritty, but I immediately liked it. I felt the sensation, familiar to me from having lived in Philadelphia, that there was a definite nonzero probability of being puked on or knifed. This set Budapest apart from our European experiences to date.

I also might have formed my opinion about Budapest on the basis of our chaotic temporary home there.

After we got ourselves on the right street, we soon found ourselves in front of a gigantic, well-preserved late-19th-century white stone building, built around a central courtyard.

Ascending its dark and slippery-smooth stairs, we were met by Kjartan, our host on the fourth-floor landing.

Kjartan is an American. He grew up in Kalamazoo in a Norwegian family - hence the name. His parents were music professors. It must run in the family, because Kjartan is, for the time being, living only off of his music.

He appeared to us wearing a leather vest with no shirt and an antique fedora, with a feather. He's a slight guy, only a little bigger than me, with shoulder-length hair, light mustache, lots of stick-and-poke ink, and vague eyes. His manner indicates that if he were any more laid-back, he would be entirely horizontal.

Kjartan greeted us and let us into the apartment, a two-story affair with a large but indeterminate number of bedrooms. About half the upper level is an open floor plan encompassing a spacious living room, filthy kitchen, and dining area.

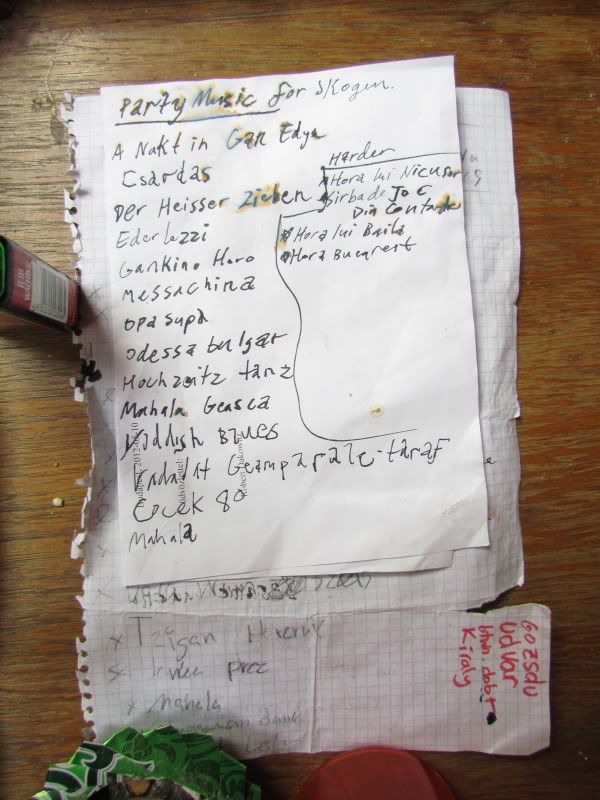

We entered to the sounds of klezmer music. Kjartan's band was practicing in the living room. Kjartan and another American "transient" named Lulu played fiddle. Kjartan's Swedish housemate Johannes rounded out the trio on accordion. They looked like gypsies. It was a strange scene.

"You can throw your stuff over here," Kjartan said. "Or wherever," he added after a thoughtful pause.

"How many CouchSurfers do you have tonight?" I asked, eying the personal articles strewn around the room.

"Three, besides you, I think. You're lucky. Last night we had like ten. How long are you staying again?"

A girl stepped out of the bathroom in a towel and smiled at us. An Asian guy with a John Waters mustache and suspenders sat on a stool, devotedly texting.

"I think we should only do that part two times," said Lulu, looking up from their sheet music.

"Two times it is, then," Kjartan replied.

A different girl walked up the stairs into the disarray of the kitchen and started boiling water amidst the stacked dishes. "I knew it was a bad idea to stay out drinking last night," she said in a thick French accent. "Now, I'm sick."

Voices mingled: "Do me a favor - can you Google search 'squat Budapest'?"

"I don't know if you've ever been wearing a costume made

out of trash while on acid in a park in New York City, but it's an

experience. I was having shamanic visions. Jesus-esque trashy-trash

apocalypse-type scenarios."

"I don't know whose cup it is. I've been drinking from all of them."

"They

party for a living. No, I mean, really. They're, like, tourist

bar-crawl guides. Basically, they party and make a very little money

from it."

"Are you sure you're Americans? You're more like Canadians. You're too polite."

Meanwhile,

Min was tidying. "But you have to clean it," Min was explaining,

pointing at the grime-encrusted stovetop. "You'll eventually get sick

from it."

"But we're hippies," protested Kjartan. "I'd rather

just spend the half-hour a week I'd spend cleaning the kitchen learning

a new song, or doing art. Anything other than that, actually."

"...and now she's holding my yurt hostage..."

"All these spots marked on the map are great for busking."

Someone knocked a bottle of wine over, and there was a general scramble to right it and mop up the spill. Klezmer swiftly resumed.

"Have some communal wine," offered Kjartan from across the open space. "I think there's vodka around, too."

"Let's get some falafel," I said to Jenna. We walked out of the concentrated confusion of the apartment and into the more diffuse one outside.

I felt, almost against my will, a prudish, parental consternation at the looseness of the apartment. It was unclear, at any particular moment, how many people lived there, who was CouchSurfing, and for how long they would be staying in either case. This judgment was unreasonable, and unexpected. Only a couple years ago, I lived in a house with six other people, with a kitchen that surpassed Kjartan's in dirtiness, where on several occasions, I woke up in the early afternoon to find people I'd never seen sleeping in the living room. Maybe my uptight reaction wasn't really based on get-off-my-lawn stuffiness, and was due more to the fact that I hoped to relax and be in my element at my home base. Here, I clearly was not.

Although I came to like all of the people we met in Budapest, it was a definite culture shock - ironic considering that we were staying with an American. So when we came to the historical center of Budapest, and found it to be not very different from that of Prague, it was a surprise to see that Budapest was not all grime and decay.

|

| Not a dog turd in sight |

The reality of Budapest is entangled in my mind with our introduction to it. It's a hopeless mental jumble, like a soufflé that refused to rise. We, admittedly, didn't manage to get up to much in Hungary. There's an abundance of activities available to the traveler in Budapest: among the ones I regret skipping are the cave tours through Buda's extensive underground tunnels and caverns (the cliffs facing the river seem to be almost entirely hollow); the Memorial Park, a graveyard of Soviet-era Realist sculptures and monuments, now rusting in their clunky bravura and calculated unoriginality; and the National Museum. As it was, I saw more of the inside of Bill Bryson's A Short History of Nearly Everything than Budapest's many cathedrals, museums, and galleries.

Additionally, we only had two full days in Budapest, compared with at least three in every other city we visited. It's hard to see much in two days.

But it's not just bias that leads me to say that it is a dirtier city than the others we've seen. People look a little downcast, ungroomed, and dumpy. The buildings, except for a narrow band on either side of the river, are in a state of distressing disrepair. Occasionally, the decay seems romantic, but mostly it's depressing. I think it's due to carelessness and general poverty. Budapest seems a lot poorer than anywhere else we've been, except maybe the rural villages in the Czech Republic.

After our first night at Kjartan's, we skipped out of communal breakfast to see the city, which is to say that we drank coffee and read in a cafe down the street. We slept well enough, but I think we desired seclusion from the perpetual flux of the apartment and the socialization it demanded.

It was here that we finally made a big decision regarding the rest of our time in Europe. Jenna and I cancelled our second WWOOF commitment in France. It was the culmination of a lot of thought and discussion, originating from our lightbulb moment in Česky Krumlov, when we realized that we are the sole authors of our plans here, and aren't beholden to the schedule we drew up months ago in Massachusetts.

It wasn't a decision precipitated wholly by our wanderlust, however. The French farm had accepted us hesitantly to begin with, saying, in a tersely-worded e-mail, that they would have us, but given the lateness of the season (we'd planned to arrive in early October), there might not be much to do. Then, when we e-mailed some weeks later to confirm our appointment and update them with information about the work we did at our WWOOF farm in the Netherlands, we got no response for over two weeks. Feeling nervous, we contacted them again to get their address, and received a reasonably prompt, but again, very brief reply. They told us we'd be sleeping in a tent (this would be in October in the Alps, mind). This brevity might be chalked up, in part, to the language barrier, but it inescapably suggested indifference, as well. In short, our correspondence didn't paint a very welcoming picture. Given the previously mentioned lack of work to be done, Jenna and I felt that backing out wouldn't put them too badly in the lurch. Our e-mail politely reneging our commitment was acknowledged with a response reading "ok take care."

What this means for us is an extra two weeks of travel. The freedom to alter our plans on a whim is appealing, but it's much easier to go with the proverbial flow when your non-negotiable commitments are few and far between. We're adding a day or two in Croatia, camping or hiking in Plitvice National Park, on the recommendation of Terli (almost certainly a misspelling - sorry, Terli), a Finnish punker who was part of the amorphous group of lovable vagabonds staying at, living in, or hanging out at Kjartan's apartment. Terli threatened to kill us if we didn't go (editor's note: we didn't make it to Plitvice in the end, but we made a good-faith effort. Terli will just have to hunt us down in the U.S., I guess). We're also dipping into Italy as far as Rome, which I'm very excited about.

Returning to the thread of our stay in Budapest, we started the day with a prolonged and quixotic attempt to mail a package back to the U.S. (It didn't work; I have the package next to me as I write. I've tried to send it from no fewer than three countries, all of whom refuse to ship a box marked "Fragile," even for copious amounts of money. The decanter I bought from Jimmy, in the Czech Republic, will be keeping me company at least as far as Italy, and possibly have to come home as carry-on baggage). This took us, regrettably, up to lunchtime. We ate at Napfényes Étterem, a vegan restaurant we found on HappyCow. It presents itself as a kind of health restaurant, serving grain coffee instead of the real deal, for instance, but the food was heavy.

Allow me to digress. Veganism in the West developed out of the crunchy-granola, health-conscious New Age fringe, so for years, what little food was available to vegans was simple, unprocessed, and low-fat. Chances are, whatever it was, it would've been cooked in Bragg's Liquid Aminos. Think of the first commercially-available meat substitute, the vegan burger: a bland disc resembling nothing so much as a cow pat, and with all the appealing texture of one. But it's healthy (assuming your definition of health comes only from the FDA numbers on the back of the carton). Fuck a vegan burger, is my point. The result of this old-school vegan health obsession is that, in the mind of the average American, vegans are self-righteous nuisances: long-haired, deodorant-shunning guys who'll ruin your barbecue by bringing wheatgrass smoothies and sprouted-spelt-and-seaweed Macrobiotic salads, all the while issuing nonstop fatwas against trans-fats. Then the pendulum swung back. Vegan cooks started making hearty, high-fat and carb-heavy American-style foods like mac and cheese using the power of home food chemistry. The idea was that you could be vegan without giving up s'mores and lasagna. Much better commercial vegan meat and dairy substitutes became available, taking a lot of the difficulty out of this type of cooking. Vegan fast-food was no longer a contradiction.

But the pendulum may have swung too far, as pendulums are apt to do. Serving a sizzling hunk of fried seitan with mashed potatoes in a rich, buttery mushroom gravy, say, goes a long way towards impressing, maybe even convincing, omnivores, it is true. At a certain point, though, you may realize that you're eating a vegan version of a food you wouldn't have deigned to consume as a meat-eater. To boot, it's just as unhealthy as the traditional dish and almost certainly more processed, makes liberal use of ecologically-unfriendly imported ingredients, and, in the final balance, just isn't very good. Some vegan restaurants pursue verisimilitude to non-vegan dishes, but seem to aim for a kind of institutional-food-service take on them. To overwhelm with creaminess and fat seems to be the goal.

Needless to say, not all vegan restaurants are doing this. The two best restaurants in the Philadelphia area, Blue Sage and Vedge, both use almost no meat substitutes or processed foods. They're both very expensive, though, and on the cutting edge of vegetarian cuisine.

Napfényes Étterem was heavy in the sense that, while everything was tasty, it lacked restraint and subtlety. Everything was delicious (especially the French onion soup), but a lighter hand with the sauces and "cheese" would have been welcome. Jenna's pasta was especially drowned in soy dairy, but had the lack of nuance I'd associate with an Olive Garden Alfredo (N.B., I'm not positive I've ever eaten Alfredo at an Olive Garden, I'm just extrapolating). Were Napfényes serving "real" versions of these dishes, they would probably have more distinctiveness. It would be nice to see the same care taken in vegan cuisine.

After lunch, we walked to the Dohány Street Synagogue.

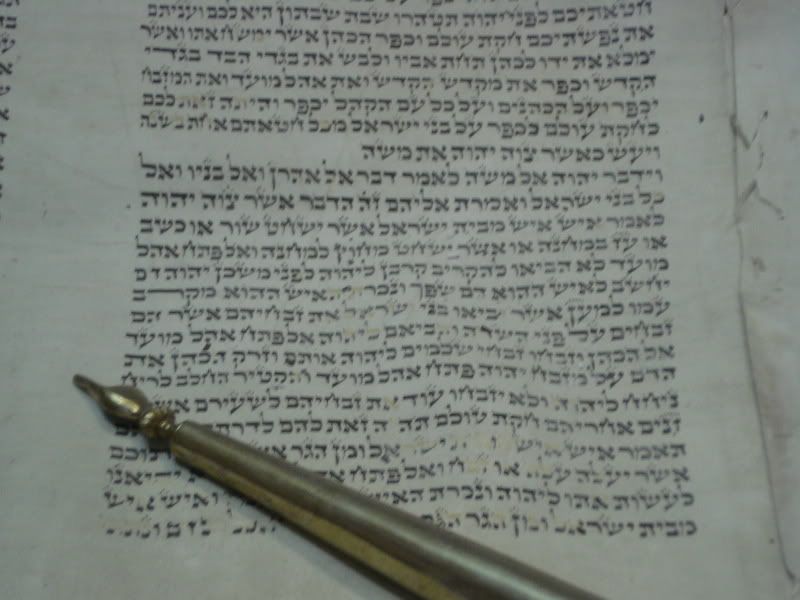

It's a working synagogue, but has a small museum as well. Although I didn't expect it to be significantly different in content from the Amsterdam and Prague Jewish Museums, I felt that this was an important stop to make.

|

| The number of torah pointers we've seen thus far must be at least in the triple digits |

The Jewish side of my family comes from Hungary, through my maternal grandfather. I don't have a lot of information about that part of my ancestry; my grandparents are dead, and my mother doesn't know or remember much about her grandmother (her grandfather, died before she was born), the one who came over from Europe. For one thing, she didn't speak much English, and died when my mother was pretty young. My grandfather, like many children of immigrants, wasn't very interested in instilling an ethnic heritage in his children or grandchildren. My aunt Joan remembers a bit more about my grandfather's family than my mother does. She has most of the family photos, for instance, and we pulled those out and talked about our family when Jenna and I were in Edinburgh.

For those of you who don't know, after a long period of consideration, I recently decided to change my legal last name to Zelman, my mother's maiden name - and the one which comes from Hungary (actually, it might not have, but more on that in a moment). It's a long and surprisingly expensive process, and one I couldn't start to undertake with only months before our trip, but I intend to start it when I have a permanent address. Kolesar, my current last name, comes from my mother's first husband, who is of no relation to me (incidentally, Kolesar is a Czech name. The preeminent animal rights activist in the Czech Republic is named Kolesar, I'm told. Seeing my last name on my passport or credit card prompted several people to jabber excitedly at me in Czech, unable to believe that I couldn't understand at least a little of the language). My mother and father were never married, so I don't have his last name. I feel strange having the last name of a family to which I don't belong, so I want to reconnect to the family name of the people I remember.

All of this is a roundabout way of saying that the Hungarian Jewish community has some relevance to me, although it's a bit muddled. Joan told me that my great-grandparents departed from Budapest, but I don't know if they lived there long, and I doubt that my family roots extend back more than a few generations there. The last name Zelmanovitz, which my grandfather and his siblings later truncated to Zelman, is not a Hungarian last name, nor is Schlessinger, my great-grandmother's maiden name. Although my great-grandmother may have said she and her husband were Hungarian, it's possible that they came from a German-speaking part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. My predecessors may never have prayed in the enormous and beautiful Moorish-style Dohány Street Synagogue (there are, after all, numerous Jewish places of worship in the city), but I can at least imagine it. It was a very beautiful building, at least, and a sentimentally-valuable experience.

In order to combat the entropy that prevailed in Kjartan's house, and to gain a feeling of control over the uncertain environment, we decided to cook a big, cheap, simple chili. Jenna cooked it up; I did dishes. It was warmly received. We found the kitchen much cleaner than we'd left it that morning, thanks to the efforts of Min, a Chinese CouchSurfer. Like us, she was a trifle bothered by the state of things, although she was much more proactive in remedying the situation than we were.

Min is quite a remarkable person. Standing all of 4-foot-10, she is a tiny beacon of self-determination and autonomy. She walked miles to and from school as a child, and then left her parents' house at an extremely early age to continue her studies. She runs her own business, which markets and coordinates the manufacturing of products ranging from clothing to motor-scooters. It's hard to believe she's in her mid-20s - she looks younger, but her accomplishments would be impressive for a much older person.

Actually, all of the people staying at Kjartan's were extremely interesting, if determinedly less ambitious. The mustached Asian guy we encountered on our first night turned out to be Jean, a fashion designer from Korea by way of Paris, although he had just finished an internship in London, which gave him the most fascinating accent I've ever heard. He's an openly queer man, coming from a culture which is very traditional in regards to sexuality. It's always a brave stance to be out, but I think especially so for Jean. We hope to meet up with him when we visit Paris in October.

|

| Morgan |

Morgan arrived the second day. She's a wonderful person, open, sensitive, and carefree to the point of recklessness. She is from Cameroon, also by way of France. She's been travelling for a long time, hitch-hiking wherever the wind takes her. I felt like we connected deeply, despite our very different lifestyles. On our final night, she let Kjartan give her a stick-and-poke tattoo reading "Enfant Perdu." She got quite drunk in nervous anticipation, then drank more as she was being tattooed, in the park after a performance by Kjartan's band. After "Enfant" was finished, she yelled that she was going to die and walked off into the dark, and was nowhere to be found. This was relayed to us by Kjartan, who seemed characteristically unconcerned. Jenna and I, on the other hand, were scared for her. Somehow, she managed to get home, because she was on the couch in the living room the next morning. She remembered begging "some yuppies" for help, and crying when they refused to render aid. I wondered, privately, if I would do the same.

Lucas was a charismatic Brazilian bon vivant making a round-the-world tour. True to my expectations of Brazilians, he rarely wore a shirt. Lucas was a former member of an ayahuasca-using religious group in Brazil, and spent a long time explaining to another interested guest the exact form that the hallucinations take. "You don't see things," he says. "You hear messages. And you can see auras, but nothing that isn't there - it opens you to what is there and you can't see." He's a master CouchSurfer. Rather than sending personal requests to specific hosts, he puts out an open request in any city he wants to stay in, and waits for hosts to invite him. Once, he said, a host paid him to stay in his house. He shrugs, in a that's-how-life-is kind of way. Some people, it seems, are special wards of the universe, coddled by fate. Lucas is one of these; the rest of us can enjoy him as an example of how to truly go with the flow.

Budapest is famous for its natural mineral baths, a product of Ottoman occupation in the 16th century. We planned to make these our destination on our second full day. We set off through the Jewish district, into the old walled section of Pest. There, the buildings were better taken-care-of and the streets were cleaner. We crossed into Buda, and walked through the hillside park near the Hapsburg-built Citadella. This was very pleasant. Paths wind lazily up and down the hills, providing amazing views of the river and the nice parts of the city. We walked for a long time, stopping on a bench to read and eat grapefruits.

|

| Left, Lucas; Right, Kjartan |

Budapest is famous for its natural mineral baths, a product of Ottoman occupation in the 16th century. We planned to make these our destination on our second full day. We set off through the Jewish district, into the old walled section of Pest. There, the buildings were better taken-care-of and the streets were cleaner. We crossed into Buda, and walked through the hillside park near the Hapsburg-built Citadella. This was very pleasant. Paths wind lazily up and down the hills, providing amazing views of the river and the nice parts of the city. We walked for a long time, stopping on a bench to read and eat grapefruits.

Unfortunately, on our descent we found that the Ruda Baths were only open to women that afternoon. The nearby Rac Baths were closed. We walked back into Pest, and walked a very long way back to the Széchenyi Medicinal Bath in the City Park (near which we met a band of our fellow CouchSurfers from Kjartan's. They had been busking for booze money in the park). These baths are supposedly more touristy than Rac or Ruda. It was open to men and women, but was very expensive, so we decided it was wiser to return to Kjartan's without bathing. Min had made dinner.

Kjartan's band was playing somewhere nearby, so the considerable group of CouchSurfers and roommates trundled over there to support them. The venue turned out to be an open-air plaza in front of a bar called Arboretum, whose schtick is to sell plants alongside beer, wine, and spirits. The band was performing as Polish Coffee for the night; Kjartan had traded his violin for an upright bass and they had added an acoustic guitarist/vocalist, an American named Laura. Polish Coffee played an American folk-traditional set, rather than the Eastern European klezmer music they'd been practicing at our introduction. The CouchSurfers arrived near the end of their set, and they were anything but tight - the result, I suspect, of too many free Arboretum beers. It was still a lot of fun.

Our train was leaving early from a station in Buda, so we walked back to the apartment, while some of the more hardy of the group went obstreperously into the night. It was some time after this point that Morgan went AWOL.

Our train was leaving early from a station in Buda, so we walked back to the apartment, while some of the more hardy of the group went obstreperously into the night. It was some time after this point that Morgan went AWOL.

So it came to pass that we left Budapest largely as unenlightened as we came to it. It was an experience valuable not so much for the unique urban culture and environment as our personal encounters. It was good for me to meet people traveling in such a haphazard way. I can incorporate, I hope, some of that freedom from expectation into our travels, while still doing it my way and enjoying the things that I like.

Leave a Reply