|

| Henrike carved our names into a pumpkin the day we arrived. Two weeks later, this is what it looked like. |

I'm writing this in a smoky basement bar in Ungdomshuset, waiting for a punk show to start. "Holiday in Cambodia" just made its third run on the PA, followed quickly by the second round of "But After the Gig," probably Discharge's worst song, pre-1985. Jenna went out to a bar with our hosts, Sofie and Rikke, and their friends - we all came here for cheap eats, but they prefer reggae to crust punk. As always when I attend a show alone, I feel bored and self-conscious, although I'm told that this reads as tough and aloof to strangers. I don't feel tough. Being a non-drinker and a non-smoker, I don't have an activity with which to passively occupy myself and consequently my aloneness seems more conspicuous. I've already exhausted the ruse of rifling through the records at the merch table. I think I like shows better in theory than practice.

Ungdomshuset is inspiring, my social awkwardness aside. You may remember a minor news story a few years ago regarding enormous youth riots in Copenhagen, stemming from the forcible eviction of a "youth center." Police cars were torched, Molotov cocktails were thrown, and protestors were arrested by the droves. The youth center was Ungdomshuset (literally, "Youth House"), a building squatted for decades before the government determined that the space would be more beneficial as a parking lot. I'm in the new Ungdomshuset; the old one, despite the riots, is now a parking lot. Everyone seems to regard this space as a neutered replica. It may even be legal now, I'm not sure. Still, I just ate a bowl of vegan chili and a cup of coffee for the equivalent of $3.50, less than it costs to ride the bus, cooked in a communal, volunteer kitchen. In addition to community dinners, the house is a venue for workshops and radical political action.

Why can't the US support this kind of autonomous alternative youth community? It seems like the violence, authoritarian repression, and individualistic egoism that destroy cooperative ventures in America must be pervasive to our culture and way of life.

It was sad to leave our farm in the Netherlands, although as a memento, I got to keep the deep, seemingly indelible stain I developed on my hands from twisting the beet greens off of the roots. More materially, we also took a few pounds of striped and colored beets and a bouquet of exotic carrots to our hosts in Denmark.

The upside to leaving Henrike's farm is a definite improvement in my physical health. There is, as I mentioned previously, a great deal of life on the farm, both vegetable and animal. I am, unfortunately, asthmatic and severely allergic. Although it used to send me to the hospital every few months as a kid, my asthma isn't all that noticeable under ordinary circumstances, but working on the farm, with its myriad pollens, dusts, and danders, exacerbated my immune oversensitivities. I was sniffling constantly, despite daily doses of decongestants and anti-histamines, and I was so frequently asthmatic that I needed to start taking an inhaled steroid, which I haven't needed to do for several years. I'm just glad I had the foresight to bring it from the U.S.

Unfortunately, my daily medication didn't keep my asthma completely under control, and I was using my "rescue medication," an inhaled medication that acts quickly to open the airways during an asthmatic attack, multiple times a day. Consequently, I started running low on it. That's bad news, of course, because Jenna and I would be leaving the farm soon - too soon to have my mom send me another inhaler - and wouldn't be in any one place more than a few days until our farm in France. I decided to schedule an appointment with a doctor in the Netherlands. I didn't know if my crappy budget insurance would cover it or not, but I would rather eat the cost of a consultation and prescription than run out of medicine. On Tuesday, our last day in the Netherlands, I biked to Ens and had a brisk, businesslike consultation with a doctor, and ten minutes later, left with a fresh inhaler. It cost about $30 for everything; they didn't ask for my insurance information, and I didn't volunteer it. They probably wouldn't have covered an international prescription anyway. Perhaps because healthcare is a public business in the Netherlands, the doctor didn't do an unnecessary evaluation to determine if I was really asthmatic, which an American doctor would have almost definitely performed. Instead, he sensibly considered my mostly empty inhaler as sufficient evidence that I could be safely given a fresh one.

Henrike sent us off with an early dinner of waffles (she even made a batch of vegan waffles) with strawberry mush and creme fraiche, for those inclined that way. We took an overnight train to Copenhagen, which was uneventful.

We arrived in the morning on Wednesday. Our first requirement was coffee, which we satisfied at a sort of generic-looking shop across the street from the train station. Here, we were introduced to the $4.00 cup of coffee, followed shortly by the $8.00 bus ride (for two of us, but the point stands), and the $6.00 loaf of bread. Perversely, beer is as cheap or cheaper than in the US.

I've identified two ways in which the United States beats the pants out of any European nation I've thus far encountered. The first is in the attentiveness of our restaurant staff. There's no two ways about it: the service sucks here. There's no division of labor: the person who greets and seats you will also serve you, clear your plates, and probably fix your americano. Wednesday night was my five-year anniversary with Jenna. We went out to a really fancy vegan restaurant, Firefly Garden. The nouveau-cuisine dishes were of the type that cooks hope food critics will describe with adjectives like "playful" and "deconstructed." There were reductions Jackson-Pollacked around everything, edible flowers, all the food stacked up in little piles in the center of the plate, polished river stones as decorative garnish, etc.

As nice as the place was, our waiter forgot to bring water (we ordered it; it almost invariably costs extra, we've learned), left dishes on the table long after we were done, and had to be signaled to bring a check. He was a perfectly nice guy, it's just that the overall benchmark is low.

The second, more important, advantage that America enjoys over Europe is its cheapness. Everything is more expensive here, more or less depending on where you are. The indulgence of a vegan doughnut or an extra appetizer is a matter of $3.00 in Philly. Either could set you back $8.00 here. Will I ever stop being amazed at how expensive things are in Europe? Probably not.

As a correlary to this point, I think Europe's reputation for culinary supremacy is overstated, or rather, is completely irrelevant to me. As a poor vegan, I couldn't care less about Michelin Starred French cuisine. The food available to me at my price range is on par with American food in quality, but more expensive.

We decided to split our CouchSurfing time between two hosts. We had contacted a couple who were unable to host us themselves, but went out of their way to ask their friends if they could host us. They put us in touch with Sofie and Rikke, who were really nice folks and great hosts. Jenna and I decided to stay with them two nights, and then stay the third night on the boat with a dude named Martin. We, unfortunately, couldn't stay in the housing co-op, having already committed ourselves for all three nights.

After coffee, we walked to the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek. Originally a private collection of Carl Jacobsen, the heir to the Carlsberg Beer fortune, it houses a massive collection of ancient and classical Mediterranean statues and artifacts, along with a collection of 19th-century art. In 1882, Jacobsen opened his home to the public, but in 1888, he donated his collection to the state, on the condition that a suitable building would be erected. The museum is exquisite, prominently featuring a winter garden, enclosed in a vast glass dome. The workmanship displayed in the marble floors, stained glass windows, and carved wainscotting is probably unavailable at any price today.

Due to its proximity to Tivoli Gardens' roller coasters (how expensive must that tourist trap be! They're spendy in the US; one shudders to think what a park concessions corn dog costs in Denmark), the Glyptotek has the quirk of having the sound of screaming people echo the halls.

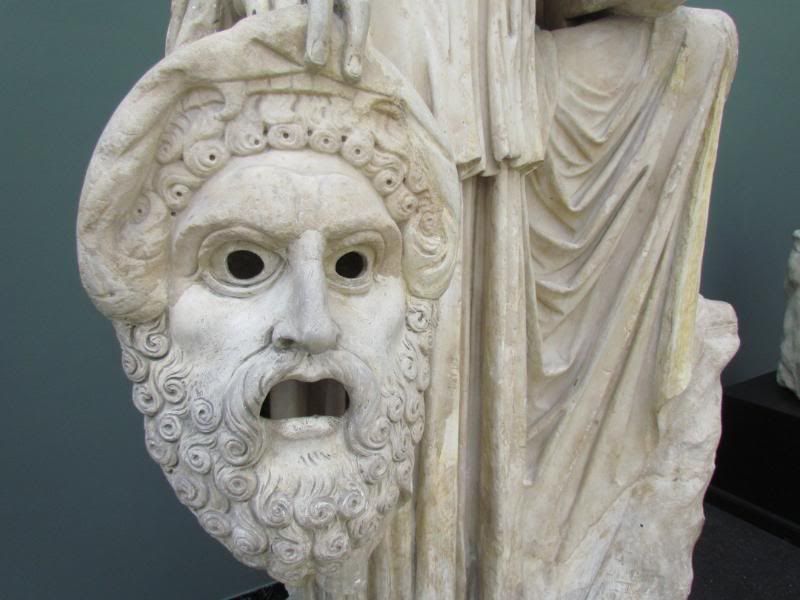

|

| Kneeling Barbarian, Rome c. 20 BC |

|

| Melpomene, Monte Calvo 2nd Cent. CE |

|

| Cuirass Bust of Caligula, Rome 37-41 CE |

|

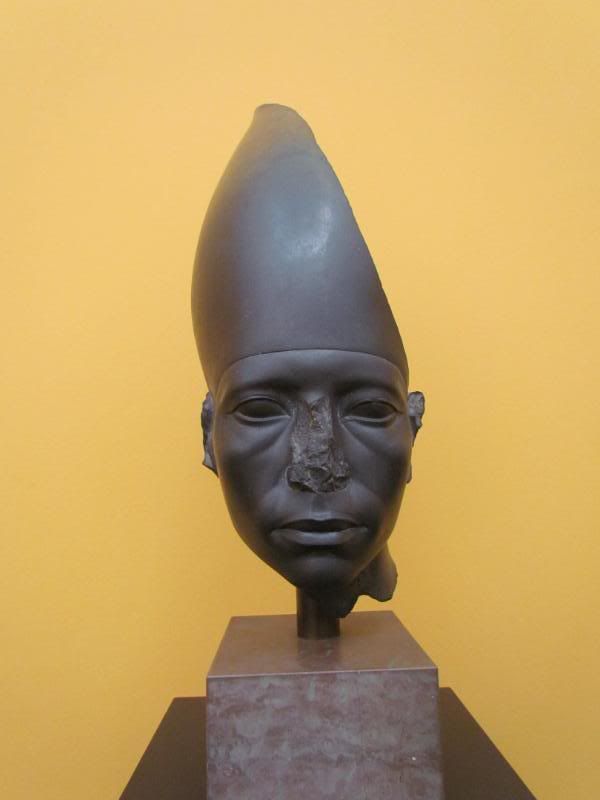

| King Amenemhat, Egypt c. 1800 BCE |

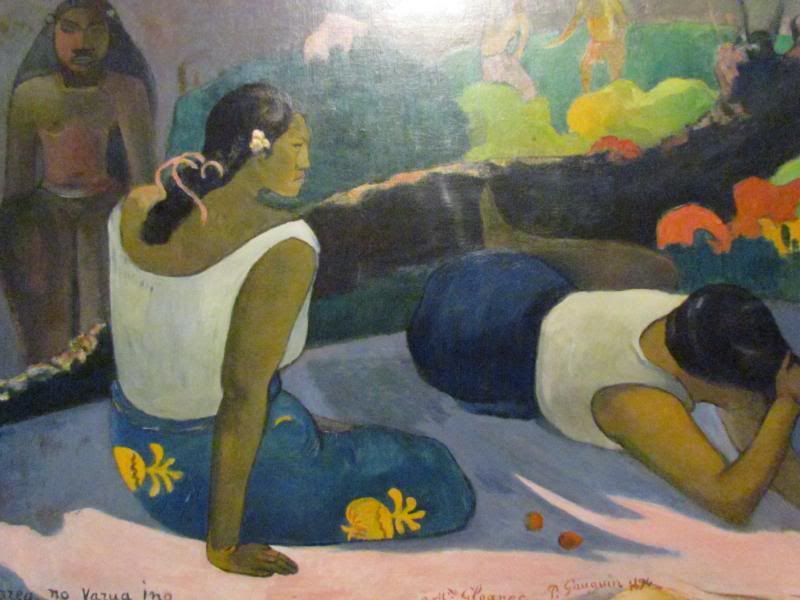

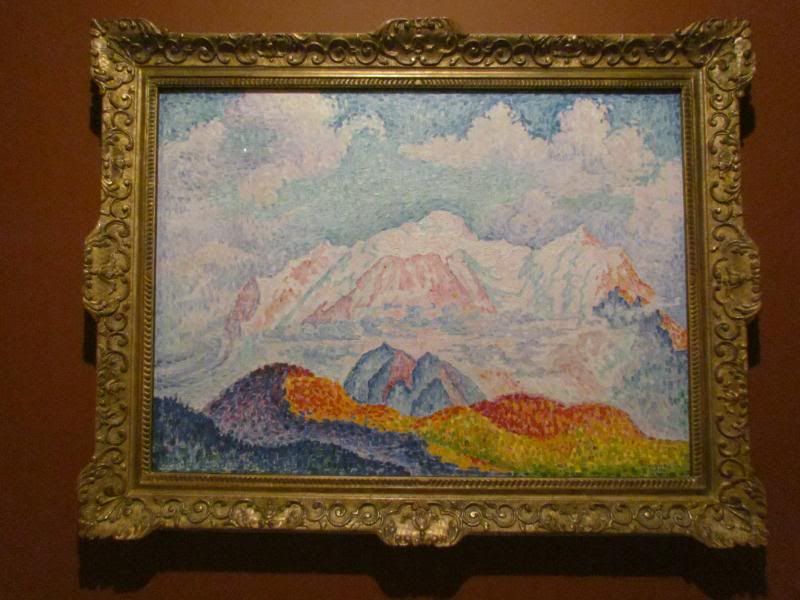

The 19th-century art was biased towards sculptures, including a really large collection of Rodins, but there were also a few galleries of French and Danish paintings.

|

| Toilette After the Bath, Degas |

|

| Reclining Tahitian Women, Gauguin |

|

| Ophelia, Agathon van Weydevelt Léonard |

|

| Resting Model, Constantin Hansen |

|

| View of Mont Blanc, Signac |

|

| Bronze study, Degas |

|

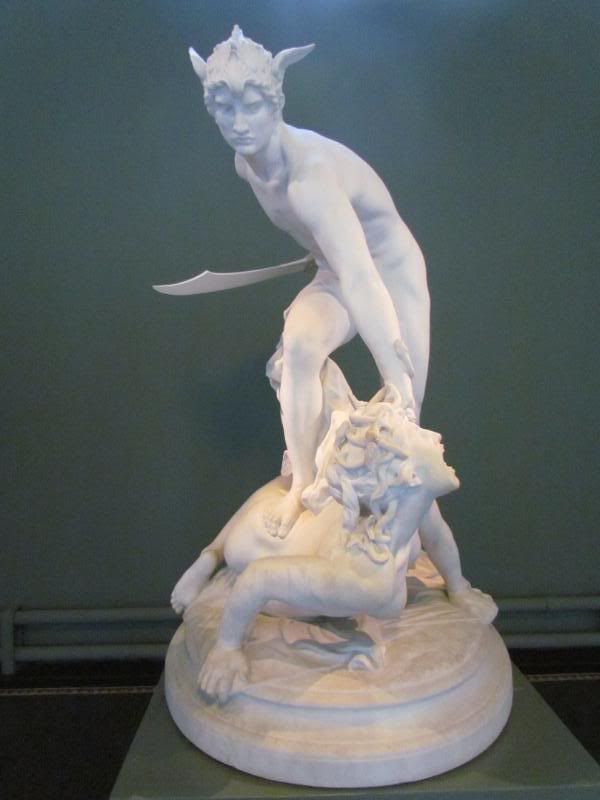

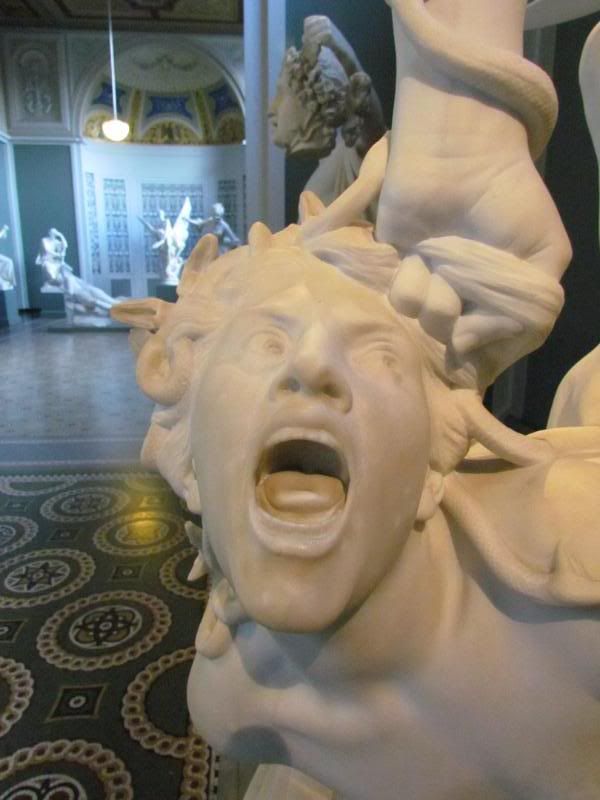

| Perseus Slaying Medusa, Laurent-Honoré Marqueste |

|

| Young Girl Braiding Her Hair, Berthe Morisot |

|

| Danaid, Rodin |

We saw Christiania on Thursday (today, the 6th, as I write this). Christiania is one of the main reasons I wanted to get to Copenhagen, even though it's a detour far north of the rest of our European travel. It was a fascinating experience. Christiania was formerly a naval base, which, having laid vacant for some years, was occupied in 1971 by counter-cultural types and declared an autonomous zone. It's been continuously squatted since, and many new buildings have been built by residents. Its history is marked by conflict, both internal and with the municipal government. Christiania has a booming and very visible soft drug economy, in direct contravention of Danish law, which has been tolerated to greater and lesser extents by different local governments. Hard drugs were, for a time, a major problem for the community; additionally, Christiania residents were, for a while, in a state of war with a biker gang who sought to take over the drug distribution in the area. Drug conflicts have led to several murders since Christiania's inception. In short, Christiania has its problems. On the other hand, the residents have responded very effectively to these problems, fixing them without recourse to outside authorities. Now, it's a safe, even touristy, attraction. It was quite busy.

Christiania is a mixture of the stone barracks which were there when it was first occupied, and the houses and shops erected by subsequent residents. There are art galleries, bakeries, restaurants, grocery stores, vegetable stands, an indoor skate park, a hardware store, and a bike factory. All the buildings are cheerfully graffitied. The main street is Pusher Street, so named because it's the center of the "Green Light District," the drug marketplace. Several years ago, the government asked Christiania to make the drug trade "less visible." The dealers responded by covering their kiosks in camouflage netting. There are no photos allowed in the drug-dealing zone. Outside of this area, Christiania is mostly residences, customized in unique and whimsical ways. Happy, oblivious dogs run free. The atmosphere in Christiania is very different from the rest of Copenhagen: it seems to strive for a happy, sun-dappled hippie vibe, akin to a fine summer day in Vermont, but it falls short of this pleasant serenity. Behind the bold, primary-colored houses and dreadlocks and overalls, there's a hard edge of distrust and a willingness to fight. The day-to-day living of the residents is more interesting to me than the cafes and market stalls. I have a lot of questions. For instance, what kind of people choose this life? Do most community members work inside Christiania? Is Christiania's internal currency actually prevalent among the people who live there, or do they prefer the kroner? Are food and other goods free to residents? If not, is it really a commune?

I thought a lot about The Dispossessed when walking through Christiania. In that novel, LeGuin imagines a post-revolutionary society, where anarchism is orthodoxy. The story takes place seven generations after a group of settlers breaks away from their capitalistic home planet to form an agrarian libertarian-Communist society on a satellite moon. The various mechanisms of communal labor and resource-division have been reified in the fictional society.

Christiania is possibly Western society's longest-lasting example of an autonomous collective. It, too, has something of the inertia of orthodoxy behind it. What struck me was how normal everything seemed: the people of Copenhagen simply accepted that, within their city, there was a secessionist anarchist commune, and it's the place to go to buy hash and loiter. It did not seem revolutionary, or even different in any substantial way from the shops and houses around it.

Because of its status as a tourist destination, Christiania's anti-capitalism is muddied. It's true that there are no private vehicles or houses in Christiania, but so much of the economy is based on selling things - mostly drugs, really - to outsiders for profit. Even if that profit is reinvested into the community as a whole, it reflects the interdependence of Christiania on the capitalist economy outside its gates. I wonder to what extent the legalization of marijuana in Denmark would disrupt Christiania's economy.

Recently, the government has been trying to leverage Christiania residents into buying (at a very low price) the land that they've been inhabiting since 1971. Additionally, plans are in the works to build privately-owned condominiums in the area. These are bad signs for the integrity of Christiania's future. Still, it's also important to recognize that the government's desperation to introduce private enterprise and ownership into Christiania is a symbol of the commune's success. If it didn't represent dangerous ideas, the powers that be wouldn't be so eager to destroy them.

The show is over now. Being a wallflower paid off in one way: I somehow avoided being asked to pay. Three bands played; I enjoyed each of them to a degree. The second band - I think they were called Instincto - played melodic d-beat, with characteristic dramatic Tragedy-style chord progressions and goofy "epic" lead breaks. I was all, "Oh, what's up? Is it 2006 again?" And 2006 was all, "Yeah, it is. We're having a great time over here." Played out as that style is, I found myself grinning and bobbing my head like an idiot. They were from Barcelona, which makes sense, because both Ekkaia and Ictus, the bands I consider paradigmatic of melodicrust as a genre, also hail from Spain. The final band was local, kind of a UK '82 outfit, and got the crowd all stirred up. The circle pit got pretty violent, but everyone seemed to be going out of their way to take care of me - something people do frequently (but unnecessarily) when I'm the smallest guy in the pit.

After the show, I met up with Jenna, Sofie, and company at the bar. It was fun. Sofie's friend Katrine, who's a bartender there, insisted on getting me a soda. Everyone was pretty drunk. I talked politics with this really nice skinhead guy, Matt, for a while before heading home. His friend Peter was comically drunk - at the stage of mental devastation in which the will to speak is active, but the physical mechanisms of communication are just out of reach. He broke a glass, lost his hat, and spilled beer across his crotch within minutes of my arrival at the bar.

Copenhagen is a windy, serious city. A Gothic, stentorian atmosphere rules the dark Scandinavian streets and minimalist buildings in this city, where Kierkegaard appropriately rests his bones. It also brings to mind another famous Dane, Hamlet. Copenhagen seems exhausted, cynical about its own prospects, vaguely in decline. Because it is our second urban stop on the Continent, Copenhagen invites comparison to the first, Amsterdam. While Amsterdam flaunts its beauty and narcissistically courts the tourist trade, Copenhagen goes about its business, playing its cards closer to the chest. The less buttoned-up parts of Copenhagen don't quite match Amsterdam for revelry; Christiania is full of sensual pleasures, like the Red Light District, but could hardly be described as "carefree." Both cities are characterized by extreme affluence, but while Amsterdam's moneyed elite live ostentatiously in 16th-century canal houses, Copenhagen's wealthy remove themselves to distant, blemish-free cubes of modernism. Copenhagen lacks Amsterdam's gloss, but is perhaps more profound; I wouldn't say I liked Copenhagen better.

Leave a Reply